In April 2019, David Ginsberg, a Meta executive, emailed his boss, Mark Zuckerberg, with a proposal to research and reduce loneliness and compulsive use on Instagram and Facebook.

In the email, Ginsberg noted that the company faced scrutiny for its products’ impacts “especially around areas of problematic use/addiction and teens.” He asked Zuckerberg for 24 engineers, researchers and other staff.

A week later, Susan Li, now the company’s chief financial officer, informed Ginsberg that the project was “not funded” because of staffing constraints. Adam Mosseri, Instagram’s head, ultimately declined to finance the project, too.

The email exchanges are just one slice of evidence cited among more than a dozen lawsuits filed since last year by the attorneys general of 45 states and the District of Columbia. The states accuse Meta of unfairly ensnaring teenagers and children on Instagram and Facebook while deceiving the public about the hazards. Using a coordinated legal approach, the attorneys general seek to compel Meta to bolster protections for minors.

A New York Times analysis of the states’ court filings — including roughly 1,400 pages of company documents and correspondence filed as evidence by the state of Tennessee — show how Zuckerberg and other Meta leaders repeatedly promoted the safety of the company’s platforms, playing down risks to young people, even as they rejected employee pleas to bolster youth guardrails and hire additional staff.

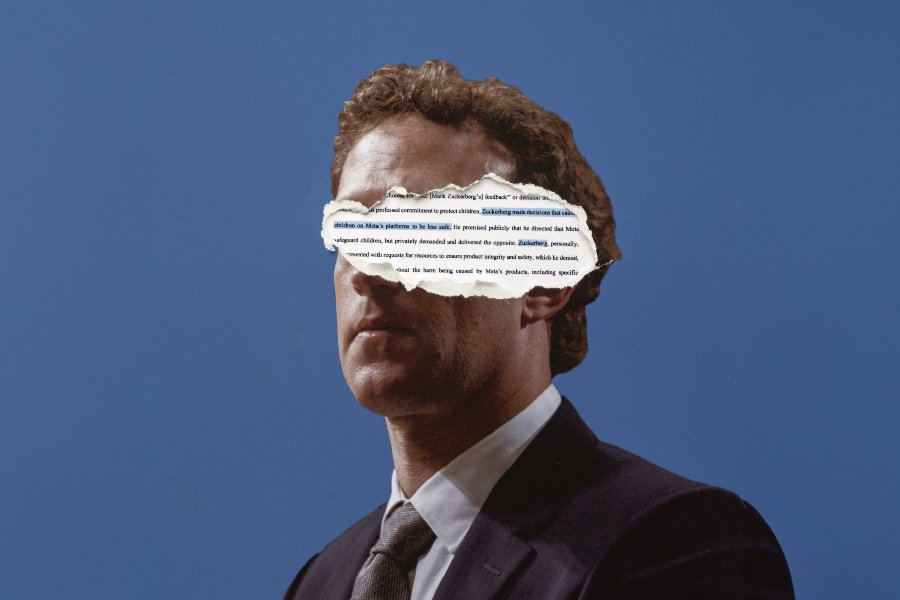

Raúl Torrez, the New Mexico attorney general, in Washington, on Jan. 30, 2024. New Mexico has sued Meta, accusing it of deceiving the public on child safety. “This is Mr. Zuckerberg’s fault,” Torrez said. Greg Kahn/The New York Times

In interviews, the attorneys general of several states suing Meta said Zuckerberg had led his company to drive user engagement at the expense of child welfare.

“A lot of these decisions ultimately landed on Mr. Zuckerberg’s desk,” said Raúl Torrez, the attorney general of New Mexico. “He needs to be asked explicitly, and held to account explicitly, for the decisions that he’s made.”

The state lawsuits against Meta reflect mounting concerns that teenagers and children on social media can be sexually solicited, harassed, bullied, body-shamed and algorithmically induced into compulsive online use.

In a statement, Liza Crenshaw, a spokesperson for Meta, said the company was committed to youth well-being and had many teams and specialists devoted to youth experiences. She added that Meta had developed more than 50 youth safety tools and features, including limiting age-inappropriate content and restricting teenagers under 16 from receiving direct messages from people they didn’t follow.

“We want to reassure every parent that we have their interests at heart in the work we’re doing to help provide teens with safe experiences online,” Crenshaw said. The states’ legal complaints, she added, “mischaracterize our work using selective quotes and cherry-picked documents.”

Meta has long wrestled with how to attract and retain teenagers, who are a core part of the company’s growth strategy, internal company documents show.

Teenagers became a major focus for Zuckerberg as early as 2016, according to the Tennessee complaint, when the company was still known as Facebook and owned apps including Instagram and WhatsApp. That spring, an annual survey of young people by the investment bank Piper Jaffray reported that Snapchat, a disappearing-message app, had surpassed Instagram in popularity.

Later that year, Instagram introduced a similar disappearing photo- and video-sharing feature, Instagram Stories. Zuckerberg directed executives to focus on getting teenagers to spend more time on the company’s platforms, according to the Tennessee complaint.

The “overall company goal is total teen time spent,” wrote one employee, whose name is redacted, in an email to executives in November 2016, according to internal correspondence among the exhibits in the Tennessee case. Participating teams should increase the number of employees dedicated to projects for teenagers by at least 50%, the email added, noting that Meta already had more than a dozen researchers analyzing the youth market.

In April 2017, Kevin Systrom, Instagram’s CEO, emailed Zuckerberg asking for more staff to work on mitigating harms to users, according to the New Mexico complaint.

Zuckerberg replied that he would include Instagram in a plan to hire more staff, but he said Facebook faced “more extreme issues.” At the time, legislators were criticizing the company for having failed to hinder disinformation during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign.

Meta said an Instagram team developed and introduced safety measures and experiences for young users. The company didn’t respond to a question about whether Zuckerberg had provided the additional staff.

In January 2018, Zuckerberg received a report estimating that 4 million children under age 13 were on Instagram, according to a lawsuit filed in federal court by 33 states.

Facebook’s and Instagram’s terms of use prohibit users under 13. But the company’s sign-up process for new accounts enabled children to easily lie about their age, according to the complaint. Meta’s practices violated a federal children’s online privacy law requiring certain online services to obtain parental consent before collecting personal data, like contact information, from children under 13, the states allege.

In March 2018, the Times reported that Cambridge Analytica, a voter profiling firm, had covertly harvested the personal data of millions of Facebook users. That set off more scrutiny of the company’s privacy practices, including those involving minors.

Zuckerberg testified the next month at a Senate hearing, “We don’t allow people under the age of 13 to use Facebook.”

Attorneys general from dozens of states disagree.

In its statement, Meta said Instagram had measures in place to remove underage accounts when the company identified them. Meta has said it has regularly removed hundreds of thousands of accounts that could not prove they met the company’s age requirements.

In 2021, Meta began planning for a new social app. It was to be aimed specifically at children and called Instagram Kids. In response, 44 attorneys general wrote a letter that May urging Zuckerberg to “abandon these plans.”

“Facebook has historically failed to protect the welfare of children on its platforms,” the letter said.

Meta subsequently paused plans for an Instagram Kids app.

By August, company efforts to protect users’ well-being work had become “increasingly urgent” for Meta, according to another email to Zuckerberg filed as an exhibit in the Tennessee case. Nick Clegg, now Meta’s head of global affairs, warned his boss of mounting concerns from regulators about the company’s impact on teenage mental health, including “potential legal action from state A.G.s.”

Describing Meta’s youth well-being efforts as “understaffed and fragmented,” Clegg requested funding for 45 employees, including 20 engineers.

In November 2021, Clegg, who had not heard back from Zuckerberg about his request for more staff, sent a follow-up email with a scaled-down proposal, according to Tennessee court filings. He asked for 32 employees, none of them engineers.

Li, the finance executive, responded a few days later, saying she would defer to Zuckerberg and suggested that the funding was unlikely, according to an internal email filed in the Tennessee case. Meta didn’t respond to a question about whether the request had been granted.

Last fall, the Match Group, which owns dating apps like Tinder and OKCupid, found that ads the company had placed on Meta’s platforms were running adjacent to “highly disturbing” violent and sexualized content, some of it involving children, according to the New Mexico complaint. Meta removed some of the posts flagged by Match, telling the dating giant that “violating content may not get caught a small percentage of the time,” the complaint said.

Dissatisfied with Meta’s response, Bernard Kim, the CEO of the Match Group, reached out to Zuckerberg by email with a warning, saying his company could not “turn a blind eye,” the complaint said.

Zuckerberg didn’t respond to Kim, according to the complaint.

Meta said the company had spent years building technology to combat child exploitation.

Last month, a judge denied Meta’s motion to dismiss the New Mexico lawsuit. But the court granted a request regarding Zuckerberg, who had been named as defendant, to drop him from the case.

The New York Times News Service