THE PUNDITS: BRITISH EXPLORATION OF TIBET AND CENTRAL ASIA

By Derek Waller

Speaking Tiger, Rs 599

Any discussion of the geographical surveys of the kingdoms surrounding British India will inevitably feature the one by Younghusband. Moreover, the tallest mountain in the world was named after George Everest, a surveyor-general who never set eyes upon the peak itself. The charge of Anglicanisation of Indian cartography as a byproduct of colonialism is thus sticky. But the 21st century demands attention to endeavours that remained ignored or were relegated to the subaltern sphere. Derek Waller’s The Pundits does so comprehensively.

Starting off with a detailed description of the tentative exploration of the areas straddling British India’s northeastern and northwestern borders by Jesuit and Capuchin priests, Waller meticulously documents the exploits of a group of ‘native’ explorers, unofficially referred to as the pundits, as they foray into Tibet and Central Asia at the behest of the raj. The narrative is engaging even in its most mundane sections; the chronicle of the trials, both natural — it certainly was not easy walking for days on end across cold, barren swathes of land — and political — Kathmandu, Lhasa and Thimpu were frigid and hostile in their reception of foreign visitors — is paced superbly. The clever contraptions which enabled these desi explorers to take measurements — hundred-bead rosaries, with every tenth bead larger than the rest, which enabled the pundits to maintain uniformity in pace, hollow Buddhist prayer wheels stuffed with parchment for official measurements, instruments hidden away in secret compartments in the explorers’ accoutrements — engage the readers almost in the manner of a quasi-espionage thriller.

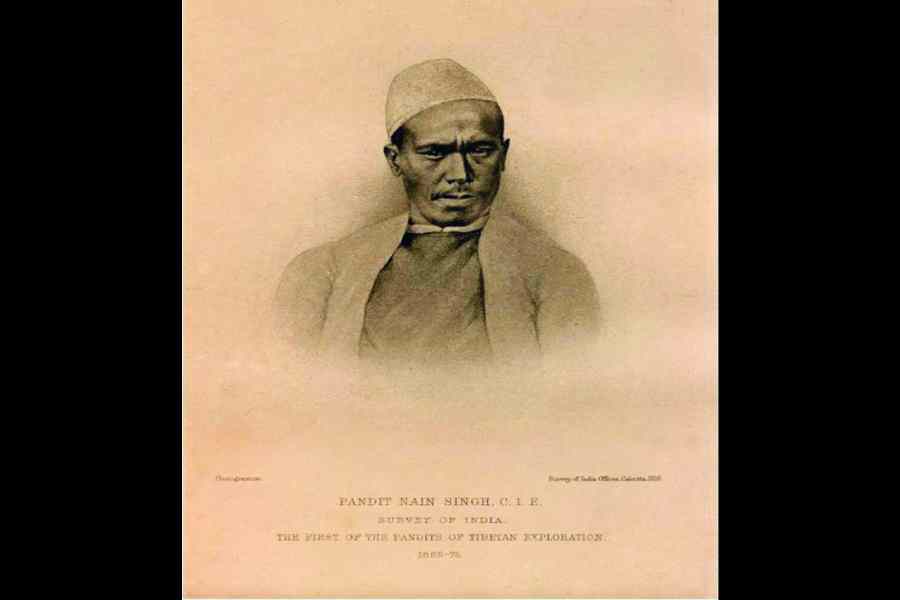

But the reason why this book deserves to be studied is that it dispels the mythologisation of the panoptic, all-pervasive Empire. The raj succeeded in ‘uncovering’ the Orient because of the intrepid, never-say-die attitude of native sons like Nain Singh, Sarat Chandra Das and Rinzing Namgyal. That their contributions went largely unrecognised and that the mapping of the subcontinent was credited to the European masters are an unfortunate confirmation of the Baconian truism that ‘knowledge is power’. Waller splendidly illustrates how the rational European used the non-threatening racial identities of the supposedly less intelligent indigenous explorers to gain access to geographical spaces from which he had traditionally been debarred, all the while not trusting them enough to gather data independently and going to great lengths to ensure “that the pundits would not be able to falsify their data.”

In his introduction to Orientalism, Edward Said writes, “Orientalism is premised upon exteriority, that is, on the fact that the Orientalist … renders its mysteries plain for and to the West.” And so these native explorers aided the British in unravelling the mysteries of Tibet. This is not to say that the officers at the Trigonometrical Survey of India were uncharitable — several pundits were awarded medals and mentioned in gazettes. But “all such widening horizons had Europe firmly in the privileged center”, which is why The Pundits is subtitled “British Exploration of Tibet and Central Asia”. The discerning postcolonial reader will know better.