A THOUSAND TINY CUTS

By Sahana Ghosh

Yoda, Rs 699

Sahana Ghosh’s book presents a disturbing picture of the dehumanisation of life in a borderland. Her study area is North Bengal, broadly the territory that once constituted the princely state of Cooch Behar. At the time of Partition, the Rajbangsi population there wanted the kingdom to remain an independent country but ended up being divided by the Radcliffe Line drawn to separate Hindu and Muslim territories to be awarded to India and Pakistan.

Ghosh’s ethnographic approach is to live with and attempt to understand the life of the people on either side of the borderland. Her convincing narrative argues that the degradation of life here is not because of any singular event but the residue of many tiny injuries.

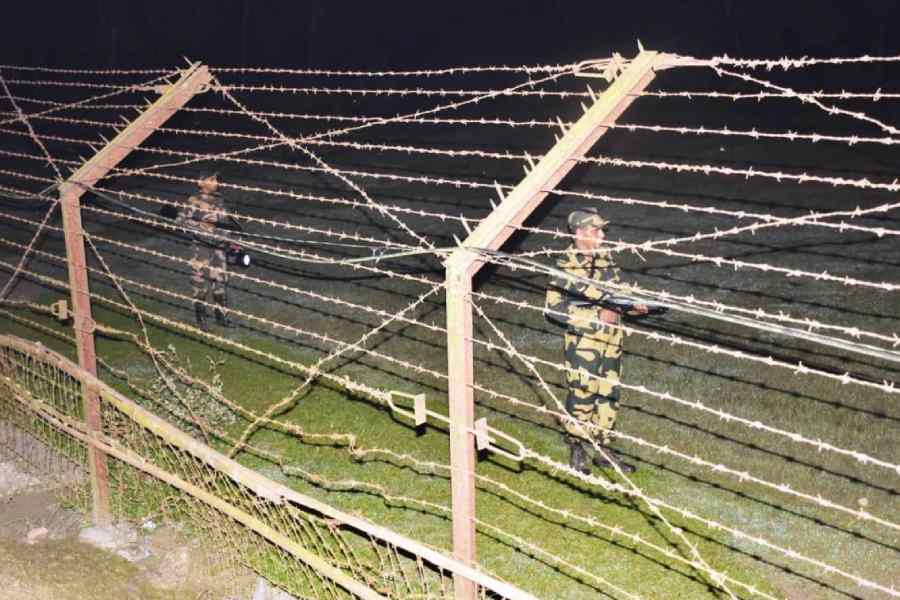

This “friendly” international border, now fenced and guarded, becomes not just a physical barrier. It is also shown as having splintered a natural economic region besides evoking nostalgia for a sense of community and kinship. Invisible to the outside world, the residents have had to acclimatise and reinhabit constantly churning social spaces.

The Westphalian State’s idea of national territory and security is shown to be in sharp contrast with the people’s understanding of traditional livelihoods and economic connectivity. On the Indian side, this is manifest in the bewilderment of Hindi-speaking Border Security Force personnel at the disinclination of the people to stick to their side of the border. This bewilderment is reciprocated by the sense of alienation among the Bengali-speaking peasantry who have difficulty communicating in Hindi.

Traditional trade chains get silently calibrated against scales of legality and morality. Hence, the trade in the cash crop, tobacco, which grows on either side of the border, continues without guilt even though it amounts to smuggling. Ganja, also a traditional cash crop grown in Rajbangsi homes, gets past the guilt screen too. However, some would not touch cattle trading for this is seen as immoral.

Gainful employment avenues are scarce and young men are expected to look for employment in cities. Those who do suffer the stigma of being illegal immigrants at their workplaces; those who remain behind are constantly fearful of being seen as informers of the neighbouring country. SIM cards of both countries work on either side and there is nothing illegal about their transborder usage; yet, people are fearful of possessing the SIM card of one country in the other.

Even marriage prospects are warped. Young men are increasingly finding it difficult to get brides from settlements away from the borderland; likewise, dowries expected from young women wishing to marry away from the borderland become prohibitive.

The book is a call for people to open their eyes to the twilight world of borderlands transformed grotesquely by these numerous tiny cuts. The plight is summed up in the foreboding verdict of a BSF personnel interviewed by the author: “... here the

soil itself is bad, corrupt, and corrupting.”