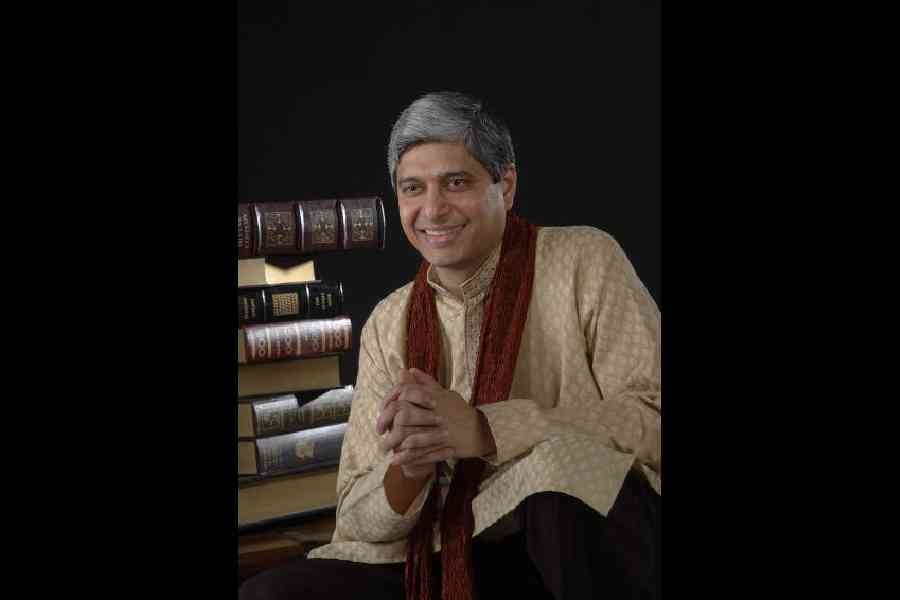

Vikas Swarup, the man behind the story of Slumdog Millionaire, returns to make a splash with a new novel, The Girl with the Seven Lives, after a decade. The celebrated, now retired Indian Foreign Service officer who picked up the pen and delivered a global sensation with his book Q&A that was adapted to the screen for the Oscar-winning film Slumdog Millionaire, based on the quiz show Who Wants to be a Millionaire?, talks to Julie Banerjee Mehta about his craft, his attraction for human stories from “ground zero” and a stellar career in diplomacy.

When you were growing up, what did you want to be?

Growing up in Allahabad, I was always surrounded by books, thanks to my grandfather who had a magnificent 10,000-book library and who instilled in me a love for literature. My earliest memories include spending time in my grandfather’s extensive library, where I would lose myself in stories of faraway places. There also used to be a lending library called Anil Book Depot from where I would borrow crime and mystery novels at the good old rate of 25 paise per day and I would try to finish the book the very same day! Though I once considered following in my family’s footsteps as a lawyer, my mother put her foot down. There were already so many lawyers in the family (including my mother herself), that she wanted her three sons to pursue other options. I was drawn to the world of diplomacy, animated by a desire to explore different cultures based on all the books I had read as a child, and managed to join the Indian Foreign Service in 1986.

What was it about human beings that made you curious about them? In all your writings — Slumdog Millionaire/Q&A, and now The Girl with the Seven Lives — you evince an uncanny talent to see the seamier side of life and reveal a life that is raw and brutal. Is this how you conceptualised the lot of human beings always, or did you grow into this vision later in life?

I’m particularly drawn to the stories of those living at what I call the ‘ground zero of human survival’. There’s something incredibly compelling about the resilience of people who, despite facing overwhelming challenges, continue to hope for a better future. These are the stories that truly resonate with me because they reflect the raw, unfiltered realities of life, yet also highlight the indomitable spirit that keeps us moving forward. My interest in these narratives grew over time, influenced by my observations as a diplomat and my desire to give a voice to those who often go unheard.

At what point in your life did you feel you wanted to write? Was it a particular image that set you off on the Slumdog story? Can you explain to your readers your process of writing?

Interestingly, I never thought I had a novel in me or that I could be a writer. I never had the urge to write until I was posted in London between 2000 and 2003. There, I saw some of my friends in the Foreign Service trying their hand at fiction, and that motivated me to take on the challenge myself, just to see if I could do it. But I wasn’t interested in generational family sagas or magical realist fables. I wanted to write something off-beat. And then it struck me, why not tap into the global phenomenon of the syndicated televised quiz show, inspired by the phenomenal success of Who Wants to be a Millionaire? The idea came about quite suddenly. I had read a news report on how slum children in Delhi had begun using a computer entirely on their own, under a project called ‘Hole in the Wall’. And then there was the scandal of Major Charles Ingram who was caught cheating on the British version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire? So I thought it would be a good idea to juxtapose a quiz show offering a massive prize amount with the life story of a rather untypical contestant — a penniless orphan who has ‘street’ knowledge as opposed to ‘book’ knowledge. That is how Q&A was born.

My writing process is both deliberate and introspective. Once an idea has germinated in my head, I let it stew in my mind for months. During this period, I flesh out the arcs of each of my characters, exploring their motivations, challenges, and growth. After this, I dive into detailed research to ensure authenticity and depth in the story I’m about to tell. Only then do I begin writing. By the time I put pen to paper, the story has already taken shape in my mind.

I never write with the intention of my book becoming a film one day. But, yes, people say that I do write in a very ‘visual’ way, which perhaps makes it easier to translate my books onto the screen.

Different writers have different comfort zones about when they write, where they write, follow a strict schedule.... Is writing a lonely endeavour you seek for your calmness of spirit?

Writing, for me, is a solitary endeavour that I find both challenging and calming. I prefer to write in my study, surrounded by books, where I can immerse myself fully in the world I’m creating. Incidentally, I have writer’s cramp so I don’t ‘write’, I ‘type’ directly on my PC. Writing in the quiet early hours of the morning is often when I’m most productive. The solitude allows me to connect deeply with my thoughts, providing a sense of peace and the ‘clear horizon’ that’s essential for my work.

Can you recall a couple of anecdotes from your life as a diplomat which influenced your work?

Diplomacy has undeniably shaped my understanding of the human condition. In my very first posting in Turkey, I was sent off to the border of Turkey, Iraq and Syria to rescue the Indians fleeing from Kuwait after the first Gulf War. One experience that profoundly influenced my work was in South Africa, where I saw the enduring impact of apartheid. It highlighted the deep injustices that persist in our world and, perhaps subconsciously, inspired me to write stories that give voice to the marginalised.

Your current book is very timely — in Devi, the reader finds an irreverent and innovative feminine force. In the still polarised gender dynamics and outrageous inequality between men and women today in India, do you have any hope at all for women’s empowerment?

Devi represents the strength and resilience that I see in the women of India today. While the struggle for gender equality, and especially for women’s safety, is ongoing, I’m optimistic that we are moving in the right direction. The younger generation is questioning outdated norms and pushing for systemic change. However, true empowerment requires more than just legal rights; it demands a shift in societal attitudes, our patriarchal mindset, and greater access to education and opportunities for women.

Does writing give you an avenue to think about new ways to dissolve differences and hatred between cultures?

Literature has a unique power to unite people by transcending the boundaries of culture, geography, and time. We make sense of our world through the stories we hear and the stories we tell. Through the stories, we gain insight into the lives, struggles, and triumphs of others, fostering empathy and understanding. Good literature can reveal the commonalities in our human experience, highlighting universal themes like love, loss, hope, and resilience. By immersing readers in different perspectives, literature challenges stereotypes, breaks down prejudices, and encourages dialogue. It creates a shared space where diverse voices are heard and respected, ultimately bringing people closer together by reminding us of our shared humanity.

Tell us about your next writing project....

I have several ideas brewing, including a non-fiction project. However, I’m waiting to see the response to The Girl with the Seven Lives before committing to my next project, whether it’s fiction or non-fiction. The reception of this book will help guide my decision on what direction to take next.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life, and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College