Book: MOTHER INDIA

Author: Prayaag Akbar

Published by: Fourth Estate

Price: Rs 499

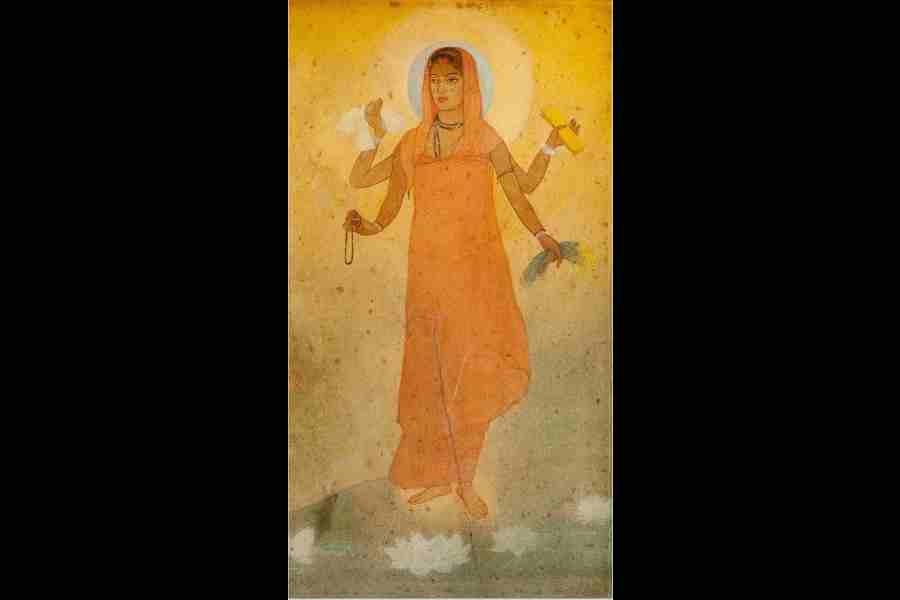

Who is Bharat Mata? Is she the figure eulogised by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay in “Vande Mataram” or the ascetic figure conjured up by Abanindranath Tagore in his painting, Bharat Mata? While Bankim’s words and Tagore’s image — both have religious undertones — have for long been pressed into the service of patriotism, they fall short when it comes to evoking the hate-filled, shrill, nationalistic fervour that gets subscribers for right-wing propagandists on YouTube.

This is why Mayank turns to Nisha.

Mayank is an assistant to one Kashyapji, a moustachioed man who runs a right-wing YouTube channel and wishes to go viral. Nisha is a girl from the forested hills of Uttarakhand who works as a salesgirl in an upscale Delhi mall. One day, in a hurry to concoct a viciously communal GIF showing Bharat Mata under attack from some skull-cap-wearing, stone-pelting men for his boss, Mayank happens to feed Nisha’s social media images into an Artificial Intelligence app and it throws up the required graphic in her likeness. Kashyapji gets his wish, and the video with Nisha’s likeness gushing blood as stones hit her body goes viral.

Those expecting a climax at this point would be disappointed because Prayaag Akbar’s novel is no thriller. Rather, it is a chilling estimation of how life goes on even after the world comes crashing around a person. Mother India reflects the nonchalance of contemporary collectives towards the upheavals that social media and viral content can cause in the lives of ordinary citizens.

There is no judgement in Akbar’s tone as he chronicles Mayank’s life and motivations. Even though he is a man who works for a right-wing lout, churns out fake, inciteful content and reels out propaganda that he has picked up from ‘WhatsApp University’, readers will find it hard to be angry with Mayank. He appears benign, even kind. He is misguided, but with a voice of conscience that manifests itself as a prickle at the back of his head from time to time. Akbar perfectly captures New India’s aspirational youth, their disappointments, and the pitfalls that they have to navigate through his fleshing out of Mayank’s character.

Nisha, an insightful young woman who yearns for her village even though she enjoys city life, could be a modern-day Dayamayee (from Satyajit Ray’s Devi). While villagers had flocked to the purported goddess in the film, Nisha’s deification as Bharat Mata brings the right-wing hordes to her social media account. But Nisha, unlike Dayamayee, is not conflicted; she knows that her newfound celebrity can be harnessed to her advantage. Does she find the courage to turn the tables?

The novel leaves readers with a clutch of similar questions, not just about its characters and their destinies but also about the fate of Bharat Mata in New India.