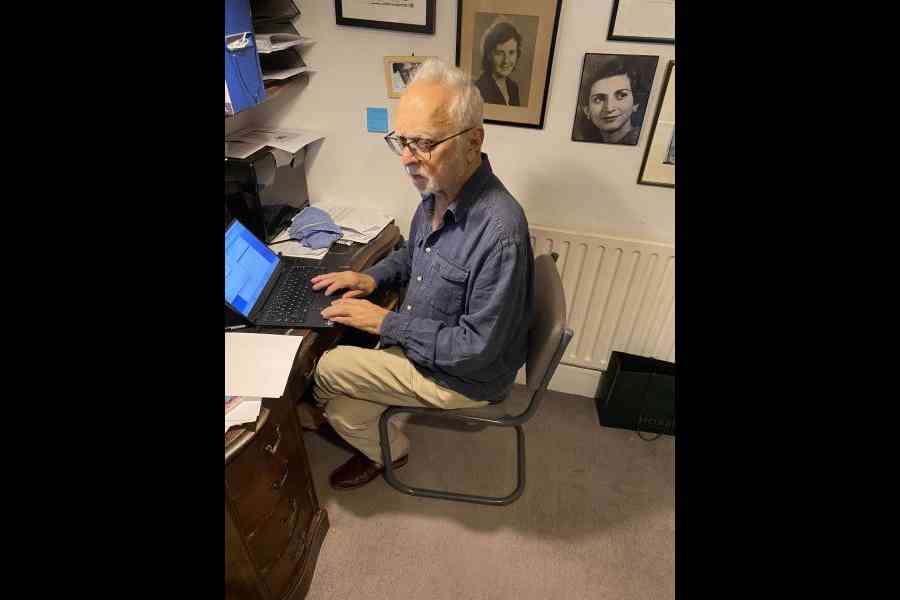

The Indo-British novelist Farrukh Dhondy speaks about his latest collection of short stories, Deccan Queen: Take Two, his migration from science to literature, and from Poona (now Pune) to Cambridge. In this conversation, Dhondy emerges as a prodigious talent who has produced novels, poems, and scripts for BBC TV programmes and films in India and Pakistan. At 80, he looks back at his experiences in London, his friendship with V.S. Naipaul, and his passion for writing. Excerpts.

It seems more appropriate now than ever before, when racial identity is knocking on your door, that your collection of short stories — written about your own Parsi community which is a minority community in India — is making a mark. What did it mean to be Parsi when you were growing up in India pre-Independence, when you reached the UK, and now when you encounter the margins yelling at the centre?

I was born in Poona, now Pune, to a Zoroastrian Parsi family. There was always in our community a sense of modest superiority as we could claim that several prominent nationalists such as Pherozeshah Mehta, Dadabhai Naoroji, and even the Communist British MP Shapur Saklatwala (my great grandfather’s brother) had led the struggle for Indian dignity and Independence. And, of course, the pioneers of Indian capitalism were Parsis. When I came to Britain, to Cambridge University, this identity was reduced to being a curiosity and was, with very little regret, subsumed into the category of ‘ethnic minority’ and part of multi-cultural Britain with Muslims, Hindus, Africans and Afro-Caribbeans. We even proudly called ourselves ‘politically black’!

How did the idea of moving to the UK accost you? How different was it than how you had imagined it? What was it like reading at Pembroke College? What were your experiences as an accomplished writer?

I suppose, like every teenager in the world, one contemplates the well-worn path or the deep unknown chasm of the future. My parents and uncles were all professionals and I had nothing to inherit and was in my teens pressured to train as a chemical engineer. It was a prestigious, fairly exclusive academic institution to which I earned a place in Bombay University but soon realised that this was not the profession in which I could spend my life. I wasted the academic years reading whatever I could get hold of, memorably Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet, everything written by Thomas Hardy and D.H. Lawrence and even the Stalinist pamphlets I bought off the pavements of Mumbai and Delhi to where I ran to my parents when I finally abandoned chemical engineering.

I still recall your brilliant BBC Channel 4 serial Tandoori Nights. You showed an incredible fluidity in many genres — poetry, drama, fiction, scriptwriting. How do you see yourself now, in hindsight? How did you make such a mark as a young writer?

I suppose it was then that the vague and certainly untenable ambition to be a writer was born. I was persuaded to study physics instead. I did a degree in sciences and with the melancholic, nagging feeling that Poona was a town that was — as they say in the Western movies — not big enough for even one of me, I applied to go abroad.

Pembroke College, Cambridge, UK, luckily gave me a place. I got a scholarship and went. I’d read so much English literature, classical and contemporary, that Britain gave me no shocks. Cambridge was certainly at the time divided into a majority of public school entrants and a strikingly rebellious contingent of working-class boys and girls who had made it through academic merit to Oxbridge. I was inevitably attracted to the latter and made friends amongst these determined meritocrats. I entered the life of the university writing for its publications, joining its drama societies and, having done two years of sciences and had qualified for a degree, switched in the compulsory third year to ‘complete my terms’ to English.

Having done a degree in quantum physics I received a congratulatory letter from the Indian Atomic Science Institute offering me a job. They were at the time making a nuclear bomb and I, with socialistic, pacifist convictions, declined. What else to do with a quantum physics and English undergrad background? The second reason was I had eloped with my teenage girlfriend Mala Sen and her parents — her father Lieutenant General Sen and her mother ‘Babli’ Bhagat — weren’t too pleased. Matters were settled when we got married in a registrar’s office in Kensington, but decided to remain in Britain with no prospects of a productive sustainable life in India.

Where do you think you really learnt the art of writing? Did you have a mentor/guide? Who were the writers that inspired you?

London was so different from sheltered Cambridge. Finding single bedsit rooms to live in was made difficult by landlords refusing to have Indian or black tenants. One encountered racism on the streets and in the pubs very regularly. I had met a young photographer who needed a journalistic writer-partner and I began to earn my living writing journalistic pieces — one on the first meetings between the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and the Beatles, at which we were the only reporters allowed in, and another notable one was the first major interview with the Pink Floyd before they became famous. Then there were interviews with Allen Ginsberg and others.

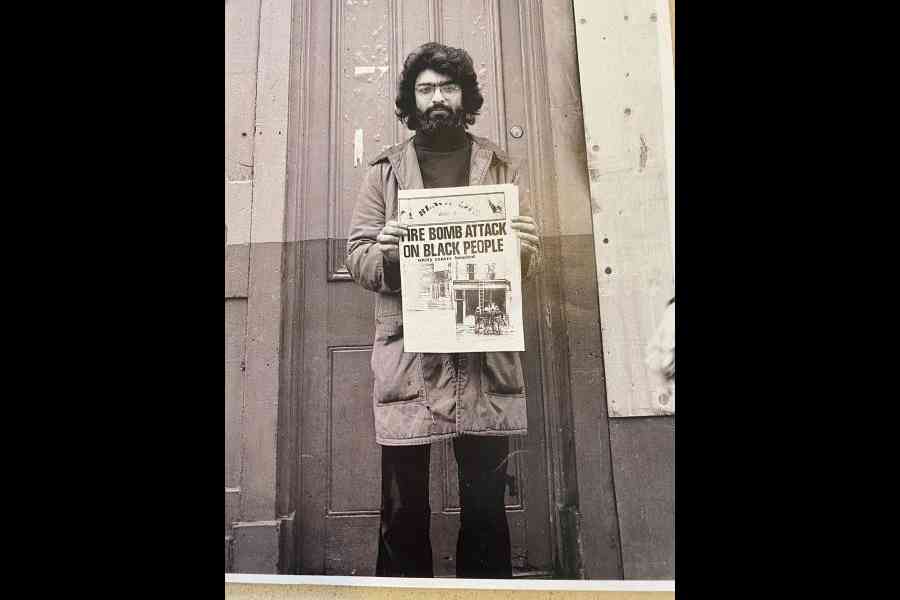

In the years I spent in London and then doing an MA on Kipling’s Indian influences for a year and a half in Leicester, Mala and I felt compelled to join radical immigrant groups — at first The Indian Workers’ Association of Leicester and then, on our return to London, the Black Panther Movement (BPM). It was writing anonymous articles in the BPM’s weekly paper on my experience as a teacher in a multi-racial school that brought about, through sheer luck, my first proper publishing book contract.

A young man in a grey suit, who had regularly read the narrative-form articles in the radical newspaper, turned up at the door of the school staffroom where I taught.

“Are you Farrukh Dhondy?” he asked me.

“Does he owe you money?” I rejoined.

“No, no,” he said.

“Are you from the police?” I asked.

He said he was an editor from Macmillan publishers and could he have a word.

Of course, he could. He said the audience for stories about multi-cultural Britain existed but the books didn’t. Would I accept a contract to fill the gap? I said: “Is the Pope a Catholic?”

That was my first commission and resulted in the publication of East End At Your Feet. Macmillan immediately asked for a second book and then a third. I wrote Poona Company, my earliest, slightly fictionalised autobiographical stories. Demands from publishers kept coming, and after about five or six published books I was approached by a drama company to write stage plays, and then by the BBC to write scripts, at first by adapting my short stories to the screen and then to writing original series for the BBC, and as I got known, for Channel 4 and even for ITV. I wrote several series — dramas and several sitcoms. Luck — and being at the right time in the right place.

I have to immodestly say that I was never taught to write and never directly inspired to churn out any particular book or form of fiction. I taught myself. When first writing film and TV, I had to look up the format, but that was just an arithmetical exercise. Of course, I was inspired by other writers, very significantly V.S. Naipaul, who became a good friend, but there was nothing in his genre that one could, or needed to, imitate. I suppose I should say my work is by default, individualistic. Unique is too strong a word.

Many contemporary writers confess that they had to leave the space of their birthplace to have the mindspace to write. How did the UK become your creative space?

I’ve certainly written most of my books, plays, TV and so on in Britain. I don’t think Britain in any way liberated by imagination though it certainly supplied the experiences from which very much of my fiction is drawn. Apart from the ‘multicultural’ — not an adjective I like as it stereotypes and chokes the work, but ‘hey’ — stories there are the second and third parts of Poona Company entitled Cambridge Company and London Company based on my life and experience in Britain. Even so, having written about 10 films set in India and Pakistan (Bandit Queen, The Rising, Jinnah, Train to Pakistan, Split Wide Open, Kisna, and others) I needed to engage with India as some of them — not all — were written and produced there.

Dhondy as a Black Panther Movement activist. He says: “In my political activist days, at about four in the morning a petrol bomb set fire to the radical Black Panther Movement’s bookshop on the ground floor. I woke up in the building’s second floor flat, trapped by the fires and had to jump from the second floor window to get out. Five black and Asian premises were fire-bombed that night. No investigation and no arrests!”

Ah! I know nothing about ‘style’. Vidia Naipaul once said to me: “Farrukh, why do people go on about my ‘style’? What is it?” And I asked him what he thought it was.

“I suppose I choose the simplest word that fits the thought,” he said. And contrasting his style with some others I once wrote that Vidia writes ‘window-pane prose’ through which you see the object beyond. Some writers indulge in ‘stained glass prose’ where the words and sentences are what you are intended to marvel at. Me? I try to be a window-pane writer, but the verdict is in the mind of the reader.

You were married to Mala Sen, who was an accomplished woman in her own right/write. How do you remember your years with her? Did you have any more serious and lasting relationships?

Mala and I divorced in the ’70s but remained close friends till her rather tragic death. She was in my teen years, and after, the love of my life — but all relationships mature and have their ups and downs. She was a remarkable, extremely generous person and very few days go by when I don’t think of her or the times we shared. Since we parted, I’ve had several relationships, and have five children, four girls, a boy and three grandchildren so far... and counting.

In a vanishing present, capturing the cultural history of a community such as yours becomes crucial. How do you retrieve memory that is always unstable? You excavate memory brilliantly in the stories in Deccan Queen. Can you say how this happens in your case?

We think, therefore we are! The rest, even the minute or second just past, is the translated experience of the senses into the cache of memory. I have, from an early age, I think, transformed immediate and past memories into stories or the ghostly plotted formation of what might become stories when the white spectral foam becomes flesh. The Deccan Queen, the train between Poona and Bombay which went in the mornings and came back to Poona in the evenings was, through my childhood, the gateway to a different city and a different dimension of mingling, a different pace of life and excitement, even in my fanciful juvenile mind, a link between peace and panic.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life and co-author of Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College