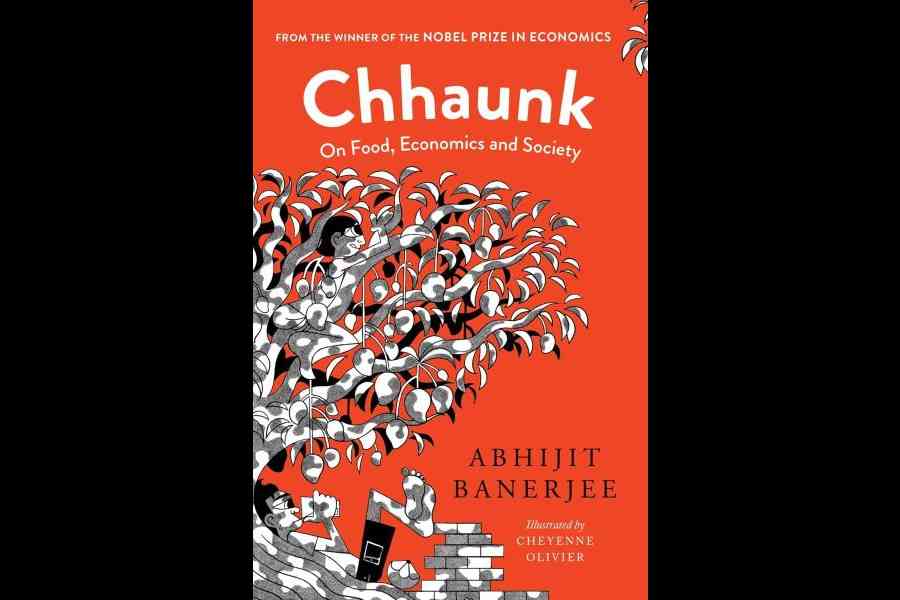

His first cookbook, Cooking To Save Your Life, published in 2021, two years after he won the Nobel Prize for Economics, introduced the world to a facet of the man that has to do with things more ambrosial. Whetting our appetite and reiterating his love for the culinary arts, Abhijit Banerjee has dropped a second book now. Titled Chhaunk, the Hindi word for tempering a meal with oil and spices for that special zing, the new read, with illustrations by Cheyenne Olivier, gives us a deep insight into the Nobel laureate’s universe — his preference for bitter food, his academic-activist mother’s views on women in society, taking part in relay hunger strike, why resolutions don’t work — and the economics of everything.

Essentially stories, the chapters highlight Banerjee’s acumen for crafting narratives that are simple, breezy and have a hint of humour as well. He aptly calls them ‘Sunday morning reads’ that are to be savoured with the recipes that he shares at the end of each chapter.

He uses food as a strong hook to break the barrier between an economist and the population at large, and has been certainly successful. t2oS sat down for a tete-a-tete with Banerjee and Olivier before the formal launch of the book at the curtain raiser event of Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival 2025. Excerpts.

Chhaunk is so different from any cookbook. While you tell stories and share recipes, Cheyenne Olivier’s illustrations add more flavour to the book. Tell us about this partnership.

Abhijit: What we do now is we want to have topics that interest both of us and that we often talk about doing a column on. Once agreed, Cheyenne would question how I will connect it to the structure of each piece, that is to connect my personal history and economics. So, I would write and then we would discuss that a bit and then I would do a draft and email it to her.

Sometimes the content would be good and sometimes it is completely incomprehensible and Cheyenne would say, ‘What are you trying to say?’ What happens is in the process of writing you discover many things; that is the beauty of writing. Often, I would start at point A, but I land in point B, which is very far away from what we had discussed.

We disagree sometimes and wrangle, but mostly she wins because in some ways my goal is to be comprehensible and since she is the person who delivers judgment on comprehensibility, I might as well listen. The fact is, whatever I write, whether I believe it or not, if people don’t understand it, it is pointless. So that is our relationship.

Cheyenne: I have no education in economics, so I always read the first piece and I would invariably remove any additional statistics that completely confuse my mind. I am not that much of a tyrant, but a lot of time when the piece is not written yet or when it is halfway through I ask what could I draw. I always try to figure out a different scene, a different set of people, because all the columns are very much about people eating and sharing food together. So it is important for me that it is not just drawing some nicely laid-out food, but a scene that tells a bit of a story. Sometimes I pick it up from Abhijit’s memory. A lot of the time he sends me the articles or the papers that he will refer to. For example, for the last piece, it was on men and women’s participation in the household. So, I read the piece and I realised that there is some idea for a visual start. Also, we do many back and forths with the illustration. He corrects if it does not seem natural or isn’t contextually appropriate.

We all know what led to the first cookbook, but what is it that made you continue with the second book? Also, in what ways did you want it to be different from the first one?

Abhijit: It is different and I think it came from the fact that in the process of writing the first book we discovered that I quite like the idea of using food as a hook for talking about everything under the sun. It is a good hook because everybody feels that I could have an opinion about it. It fits the Sunday morning read. So, people can say that even though it is by an economist it may be not too boring. It opens a window that is I think useful. And then, I think, having discovered that I decided that, well, we decided actually, that we could continue churning these out. Eventually, they helped me even with my research because it makes me think about why is this particular piece of research interesting, how does it connect to something specific in the world…. It is useful to keep renewing your connection to the world. Otherwise, it is easy in research to just keep going off on the internal logic of the research.

There are eight chapters and each chapter tells a story. Cheyenne, too, tries to tell a story with her illustrations. Tell us about the raconteur in you.

Abhijit: I think most social scientists are storytellers. To be a social scientist and really enjoy it, you have to have a storyteller inside you. I think what this does is it disciplines that. Otherwise, you can ramble, and I do ramble at dinner tables. The story can’t be endless, it needs to have a quick point and then move on to connect to things. I think social scientists by their professional commitment are storytellers and I think what this does is it makes you tell a sharper, more pointed story. I don’t think storytelling is new to social scientists.

The book is biographical in nature and we learn so many things about you. In one of the chapters you refer to something called ‘relay hunger strike’, which you took part in at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Can you tell us what exactly it is and what was it that you protested against?

It makes no sense, but it existed. It was like literally at eight we’re going to sit down for a relay hunger strike. Then, maybe at one, I’m going to relay my hunger to you and you’re going to be carrying the strike just after having your lunch. So, maybe it’s okay if you could carry the strike for six hours and, then, maybe I’ll come back after having had three bread pakoras and take the strike back from you and send you off to have dinner (laughs). We were protesting about anything and many things. It was a time when I think protesting was a healthy thing to do. I think protesting is a way to get engaged with the world; I think it was a very healthy thing.

How often do you cook?

Every day, literally. Six days a week I cook for only dinner, but I cook for an hour-and-a-half to two hours, and that’s every single day.

Lastly, moving beyond the book, since I am talking to an economist who has won the Nobel, I would like to know where India is headed economically, because while we hear that India is the fastest growing economy we also learn the rupee is making its historic falls.

I don’t know and I don’t know for a good reason, which is I think if you read the people who are I think much more informed of the Indian economy than I am, they themselves are confused. We used to be the world leader in data quality and at this point our data quality really is deplorable. We really need to have better reliable independent data sources. That’s the only way. The whole world is a bit holding its breath trying to figure out what is true about the Indian story and what is not and it’s not good for us. We should be more committed to having excellent data, excellent transparently produced data.