Book: LOVE THE DARK DAYS

Author: Ira Mathur

Published by: Speaking Tiger

Price: Rs 599

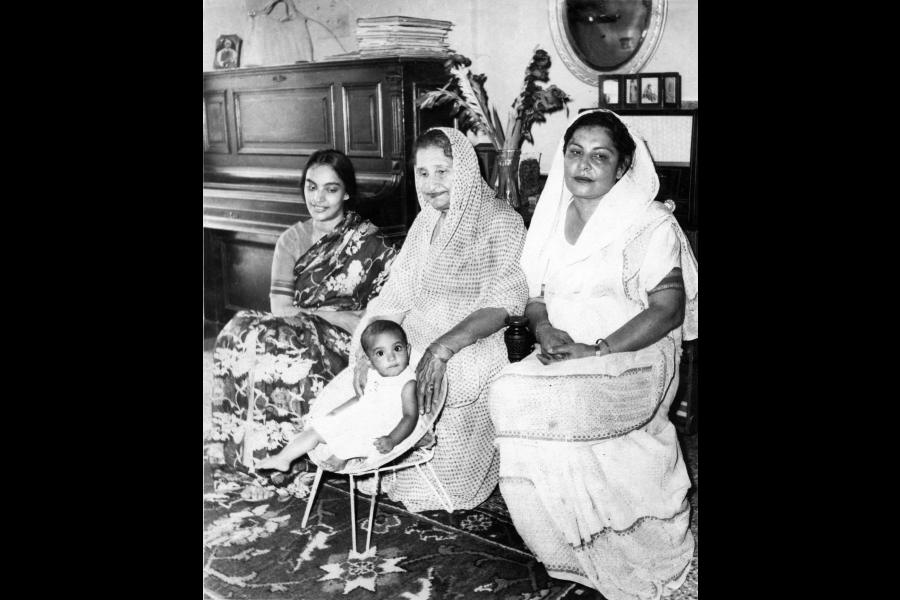

For generations, the women in Ira Mathur’s family have had qualms with one another. It is a legacy, passed on like precious cloth and jewels. Antipathy is common between mothers and daughters: as Ira has for her mother, Nur, for years of neglect and detachment; as Nur has for Ira’s grandmother, Burrimummy, for depriving her of her rightful share; as Burrimummy has for her mother, the great-grandmother, Angel (after whom Ira’s sister is named), for pulling her away from a talented life in music and getting her married to a man who would soon abandon her; and as Angel had for hers, Sadrunissa, for destroying her chances of a hopeful career in medicine in favour of marriage. Each, with her own brand of trauma, seeks the other’s approbation despite the shared disdain. It is this lineage that Ira Mathur — the “Homeless, unrooted girl; neither Hindu nor Muslim, neither beautiful nor ugly, neither Trinidadian nor Indian” — draws in her deeply moving and revealing memoir. “We all fall into the crevices created by one another’s neglect,” she writes.

Sadness, etched in the eyes of each of these women, is part of their heritage; as is aristocracy, or at least the illusion of it. For a family with abundant wealth, there is much deprivation that its children grow up with — deprived of warmth, acceptance and, above all, love. Mathur and her siblings, her parents and the reluctant grandmother move across continents, from India to Trinidad and Tobago and, later, to London and back. It is the binding colonial past of the Caribbean, America, and the African and Indian subcontinents that runs in the backdrop of Mathur’s memoir. The question of collecting stereotypes, like generational wealth, and of unlearning them, endures. Race, class and gender, hence, are pertinent characters in Mathur’s life and in her book. Her story is a testimony to the ‘personal is political’ argument as the countries emerge from their colonial influences, only to often recolonise themselves. However, the book remains, first and foremost, a personal history.

One wonders if Mathur’s writing is an attempt to preserve the lost history of her family — reduced to but a few sentences in the footnotes of a web page — as much as it is an attempt to make peace with it. With roots in Afghanistan, the Mughal era and British India, Ira Mathur’s maternal family finds representation and much redemption in the book. As for her relationships with the men in her life — father, brother, husband and son — there is much space to explore. Although they are featured and acknowledged for their influence — good or bad — in her life, there is a certain lack of depth in Mathur’s attention towards them, especially when compared to her relationships with the women in her life. Nonetheless, it is a telling memoir.

Love the Dark Days is a book that must have required great courage to write. Through writing and with much guidance from the Nobel laureate, Derek Walcott, and some influence from another Trinidadian Nobel prize winner, V.S. Naipaul, Ira Mathur comes to love the dark days of her life — an emotion drawn from a Walcott poem, Dark August. “To cancel our dark sides is to live in a blank sanitised world, where no one has the permission to examine the debris of our souls, no one is granted redemption.” As Mathur learns, “There is either truth or nothing.”