As the youngest reporter in the Paris office of the Reuters news agency, Frederick Forsyth was given a job that his older colleagues did not want to do: shadow President Charles de Gaulle. Reason: the President could be assassinated.

It was the summer of 1962 and the city was in turmoil. Algeria was on the brink of independence from France. An underground organisation called the OAS wanted to kill de Gaulle for promising Algerian independence. Every day as the French President left the Élysée Palace, the international media would follow him. As he attended his presidential functions, they would often sit around in cafes and while away the time. Sometimes they were joined by the President's bodyguards.

Forsyth, then 24, got to know them all. Listening to their chit-chat and watching the concentric circles of security around the President, he became convinced that the OAS would never succeed. He felt that the President could only be assassinated if an unknown mercenary did the job. It was the germ of an idea that would later transform itself into his first book, the international bestseller The Day of the Jackal.

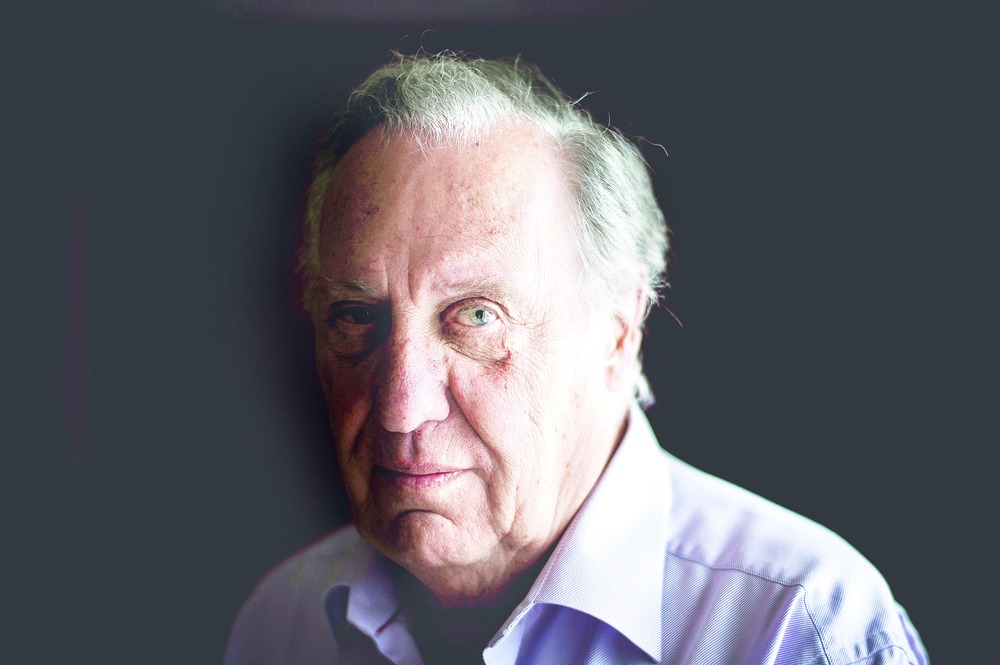

Four decades and several novels later, Forsyth, 77, has written his memoirs. Titled The Outsider, My Life in Intrigue, the book reveals that he had worked for the British intelligence for some time. The memoirs are themselves a thriller, a roller-coaster journey through a life that has been lived to the full. There are narrow escapes, beautiful women, honey-traps, spies, drug-lords and killers along the way. He laughs when I tell him that his life actually resembled that of the British fictional spy, James Bond.

"It didn't seem to me at the time," Forsyth says. "What got me into these stories was curiosity. Fortunately I could always get out, just in time. I must say there were five or six occasions when I thought I wouldn't get away."

We are sitting in his house in Buckinghamshire, looking out over his beautiful Japanese garden. The dogs are running in and out. He shows me his hand, which won't close fully following a near-fatal accident when he was 21. He was brought back virtually from the dead by a team of doctors, including a Bengali, Dr Banerjee, who sewed back his ear. The ear had been left severed on the roadside and carried back in a dish. "I wanted to thank him afterwards, but he was too shy," he recalls.

Born in Kent a year before the start of World War II, young Freddie watched the war planes criss-cross the skies. He was five years old when he sat in the cockpit of a Spitfire and knew at once that he wanted to be a pilot. "It was a dream that refused to die," he says reflectively.

He did fly, refusing a place in Cambridge, and joining the Royal Air Force (RAF) at the age of 17, becoming the youngest pilot in England. By then, he was already fluent in three languages - French, German and Spanish - all learnt in Europe, over summer holidays with families his father sent him to stay with.

But there was another childhood dream to fulfil: travel the world. Leaving the RAF, Forsyth opted for journalism. "I thought, how do you get around the world? And it was probably my father's habit of taking The Daily Express which in those days had a large corps of foreign correspondents. And I thought, 'They travel.' Here's this man reporting from Bangkok and here's this man reporting from South Africa. I would look at these stories and say, 'Dad, where's Beirut?' and he would take me to the atlas and say, 'There!' And I'd think, 'I've got to see Beirut one day'."

After a stint as an apprentice on the Eastern Daily Press in Norwich, Forsyth got his first break with Reuters in London and was sent to the Paris office. In 1964, he went to East Germany to report from behind the Iron Curtain at the height of the Cold War.

"It was an extraordinary year. It was just after the Cuban missile crisis and the assassination of Kennedy in 1963. The tension between Nato and the Warsaw Pact countries was palpable. On one side [West Berlin] there were cafes, parties, lights and dancing and the other side was black. And I was on the dark side."

Going back and forth through Checkpoint Charlie, he got to know the guards. "There was a familiarity. The guards saw me three times a week. Eventually, they got almost cheerful. Of course, the border guards were the hardest of the hard. They would be prepared to shoot down anyone trying to get out."

Could he have ever thought at the time that the wall would come down one day? "No," he says immediately. "It was not even a remote possibility. We presumed that Communism and the Soviet Union would just last."

Back in London, he joined the BBC, which sent him to cover the Biafran civil war. But he quit when his stories about the humanitarian crisis were not carried. "They were taking the government attitude, and I thought 'No, this story is not being reported accurately. It is propaganda that we are putting out'. So I left," he says. He returned to Biafra as an independent reporter and broke a story about starving children.

In his memoirs, Forsyth writes that a journalist should never be a part of the establishment. "I take that very seriously. Our job is to check on them. Talk to them, but not join them," he says emphatically.

On his return from Biafra as a broke young journalist, he sat down at his portable typewriter to hammer out his first novel. He wrote it in 35 days. The Day of the Jackal was rejected by four publishers. By the time it was published in 1971, de Gaulle was dead, and not assassinated. Yet, the book became an instant bestseller and the movie rights were signed for $3,65,000. Forsyth remembers the amount clearly, because there are 365 days in the year. His portion was 50 per cent: "I'd never seen so much money in my life."

He wrote The Odessa File and The Dogs of War, over the next two years, as his contract demanded. The novels and film deals made him rich, but he lost it all in a bad investment at the age of 49. The timing couldn't be worse, as he had just met Sandy, who would be his second wife.

"It was back to zero. So the only thing was to start again and do some more books," he says. He wrote three books between 1990 and 1995. "By 1996 I had made it all back."

I ask him if he is a storyteller first or a journalist. "I think I've always been a journalist. I don't really have a writing style. It's just like a long report," he says.

And what about the extensive research for each book? "Well, that again is journalism. If I have to describe Somalia or Bogota for the cocaine trade, I feel I have to go there. I feel that I just have to get those details right. If I want a gun, I go to a gunsmith. It takes a little more time, but when the experts say I got it right, it's great."

While researching The Dogs of War, Forsyth pretended to be an arms dealer. His cover got blown when his book was spotted in a shop in Germany with his photograph on the back cover. He was warned and managed to get out just in time.

After the publication and filming of The Odessa File, the Nazi war criminal Eduard Roschmann was arrested by the Argentine police. "When the film was screened in Buenos Aires, a man sitting in the cinema recognised the character. He said 'I know this man'. And that is how he was arrested. I thought: Wow."

His work for the MI6 is mentioned briefly in his memoirs with few details. Forsyth writes that he was happy to help the intelligence agency as they worked fairly independently from the government and were ready to go against their masters. Being a writer was a useful cover story, as he could pretend he was researching his next book.

"They [MI6] knew I spoke fluent German and they had this little errand to run," says Forsyth. "I was asked, 'Would you be so kind as to go into East Germany, pick up something and bring it back?' I thought they meant East Berlin. But no, they meant right in!"

He concedes that it could have been "very unpleasant" if he was caught carrying the packet of documents and letters.

Forsyth was also involved in the exchange of spies on Glienicke Bridge in Berlin, the bridge in the Oscar-winning 2015 film Bridge of Spies, which tells the true 1962 story of the exchange of a Soviet spy for an American spy.

"In 1964 they did another one on the same bridge. This was a British spy called Greville Wynne. Wynne was swapped with a Soviet spy caught in Britain. It was an all-British affair. I was there," he says. Did he play a major role? "Yes," he smiles.

And how does he feel about the present threat of terrorism from Islamic militants? Forsyth, who has covered terrorism in his novels The Afghan and The Kill List, says that while Islamic terrorists went back 50 years to the days of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, the present sets were different.

"All that the others wanted was free Palestine. ISIS wants to kill you. You can't negotiate with them. They don't want a piece of territory, they don't want money."

He has decided that he will not be writing another novel. The present genre of thriller writing is too technical for him. "I am not a technical man," he says. Not that he is retiring quietly. He continues his hard-hitting column in The Daily Express, the paper that sparked his initial interest in journalism, and is watching with interest the results of the Brexit campaign. "It's going to be very close," he says. It's the voice of experience speaking.