|

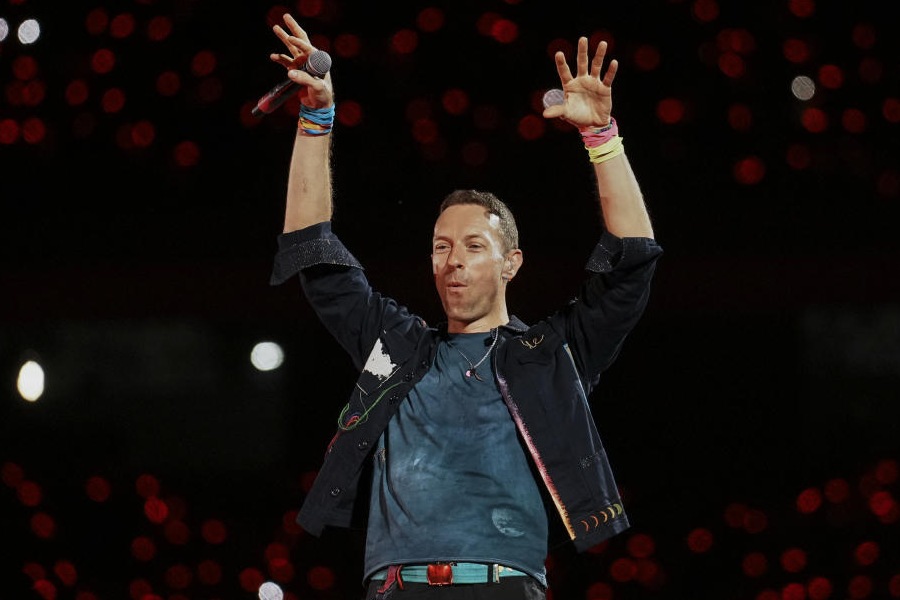

| WORD PERFECT: (Left) Indira Gandhi and her speech writer H.Y. Sharada Prasad. (Above) Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and his wordsmith Sanjaya Baru |

Albus Dumbledore, it may be said with some certainty, did not have a speech writer. At a formal gathering at Hogwarts, the school where he was the headmaster and Harry Potter a dropout, Dumbledore was asked to say a few words. “Nitwit, Oddment, Blubber and Tweak,” he said.

Dumbledore could have done with a ghost writer — a mostly self-effacing, though occasionally anything but, scribe who weaves words together in an attempt to present a speech that will stay in public memory long after the applause has died down. Indira Gandhi had H.Y. Sharada Prasad, a senior information officer that her son, Rajiv Gandhi, inherited as Prime Minister in 1984. Minister Mani Shankar Aiyar’s political career kick-started as Rajiv’s chosen speech writer. Former journalist Sudheendra Kulkarni wrote most of Atal Behari Vajpayee’s and some of Lal Krishna Advani’s speeches. And Manmohan Singh has ex-editor Sanjaya Baru.

For India, this is the season of speeches. Two leading publishing houses recently launched their compilations of some of the best speeches of modern India. On Wednesday, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh will address the nation from the Red Fort on the country’s 60th year of independence with what many hope will be a landmark speech. Congress president Sonia Gandhi will address the UN in October. The speeches will be pilloried or praised — but the wordsmiths will remain in the shadows.

That’s not surprising, for the job of a speech writer is necessarily anonymous, like that of a ghost writer. Sharada Prasad — who was with Indira Gandhi during some of her most tumultuous years — was once asked why he didn’t write his memoirs. “A man can become a ghost, but a ghost cannot become a man,” he had replied.

but going by what the speech writers have to say, it is a job that is seeped in reams of paper and days of hard work, though it does have its moments of glory. A formal speech, like the one to be delivered by Singh on August 15, is worked on well in advance. Every ministry and department sends its input on achievements and goals, and the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) sifts through it all. The draft moves from one senior officer to another — and then to the Prime Minister and back to the speech writer. “Sometimes, there are 15 or 16 drafts that go to and fro before a speech is finalised,” says a former PMO member who has scripted many speeches.

Prime Ministers — and senior politicians — have their own styles that the speech writer has to keep in mind while penning words. “Indira Gandhi was very meticulous when it came to speeches,” says former Hindustan Times and Indian Express editor B.G. Verghese, who scripted her speeches in the Seventies. “So you wrote what you thought she would be saying, keeping her own vocabulary in mind,” he says.

Rajiv Gandhi, on the other hand, made use of both speaking notes and written speeches. Mani Shankar Aiyar recalls that the speaking notes were pocket-sized cards with the key words written out almost like the lines of a verse. “There would be a line on the right of the card. In that, he would see the totality of a sentence,” says Aiyar.

Important words were marked out in yellow — by then, Aiyar adds, “the great 20th century invention, the highlighter”, had arrived. Slashes would indicate a pause. A word that needed to be emphasised was marked out. And changes were made till the last moment. Once, when Gandhi was addressing a political rally in Kakinada, Aiyar suddenly remembered the significance of a Congress session there and rushed to the podium to inform Gandhi. A card was quickly prepared and sent up to Gandhi while he was in the midst of his speech.

For Vajpayee’s speeches, Sudheendra Kulkarni had long discussions with him on any given topic. Kulkarni would be in touch with experts such as M.S. Swaminathan and C. Subramaniam on agriculture and finance. Vajpayee would refer to something like the second green revolution — mentioned by Swaminathan in many of his letters to the Prime Minister — and urge Kulkarni to weave it into a speech on the right occasion.

Manmohan Singh, too, takes advice from academics and others on special speeches, but zeroes in on the issues that he would like to emphasise. It was his idea, for instance, to talk about the legacy of the Raj at a gathering in Oxford, and on inclusive growth in Cambridge. A member of his PMO points out that he meticulously goes through every speech, suggesting changes — a habit that he shares with Sonia Gandhi.

One of Singh’s colleagues recently sat with Sonia as an aide read out a speech that was being prepared. “She went through every word, making changes every now and then. Her English is superb, but I have also seen her correct Hindi words,” says the minister.

If her husband had speaking notes, Sonia Gandhi has one serious requirement. The font size of the script is large, enabling her to read, if necessary, without glasses.

Mani Shankar Aiyar recalls how he sat with Rajiv Gandhi late at night, while the Prime Minister went over every word of his speech on the Panchayati Raj bill. “Rajiv Gandhi retired at around 1 am, but I was still there when the phone rang at 3 or 4 in the morning. It was Rajiv. ‘What are you doing there?’ he asked. ‘When the world sleeps, India awakes,’ I replied. He knew the reference, of course.”

Nehru’s opening words from his speech on India’s independence are the stuff that text-book chapters are made of. It is also a speech that figures in both Random House India’s Great Speeches of Modern India and The Penguin Book of Modern Indian Speeches. “Those were memorable speeches. Nehru’s Tryst with destiny, or the Light has gone out of our lives, or Vivekananda’s Brothers and Sisters of America became a part of the nation’s vocabulary,” says senior editor Rudrangshu Mukherjee, who compiled the Random House volume. “But very few speeches now are memorable.”

mukherjee argues that changes in the nature of politics have led to a decline in the quality of speeches. Speeches today, he argues, are more business-like, and have fewer literary flourishes. Verghese believes that the decline may have something to do with the new player in the public-speaking arena — the TV. “This is a result of the sound bite culture,” he says. “People’s attention span is lessening and news is being condensed into briefs and capsules.”

In these changing times, life is not all that easy for a speech writer. Audiences are not what they used to be, and neither are speakers. To top it, a good speech brings glory to the speaker, but a controversial one often boomerangs on the writer. Aiyer, for instance, was held responsible for Rajiv’s infamous words, “Nani yaad dila denge” (you’ll remember your grandmother), though the former speech writer says that he had nothing to do with it. Kulkarni was politically pelted when Advani spoke on M.A. Jinnah’s concept of a secular nation in Pakistan two years ago — a speech that led to Advani’s ouster as BJP president.

But Kulkarni has always held that his stint in Vajpayee’s PMO gave him immense satisfaction. For him, it was not just a job but a part of his political activism. His discussions with Vajpayee on issues such as highways and roads led to policy formulation. It was also he who had urged Vajpayee to publish a message on New Year’s Day — leading to Vajpayee’s famous musings from Kumarakom. “A speech writer can also be a great agent of change,” says a former PMO member.

For most people, though, the speech writer continues to be a faceless entity. And speeches in the time of haste draw their share of sneers. Just the other day, a cartoon in a daily had an aide asking his political master if there was a need for a new speech on Independence Day. “Since the audience will be new, we could use last year’s speech,” he said. Clearly, the aide in the cartoon was no speech writer.