|

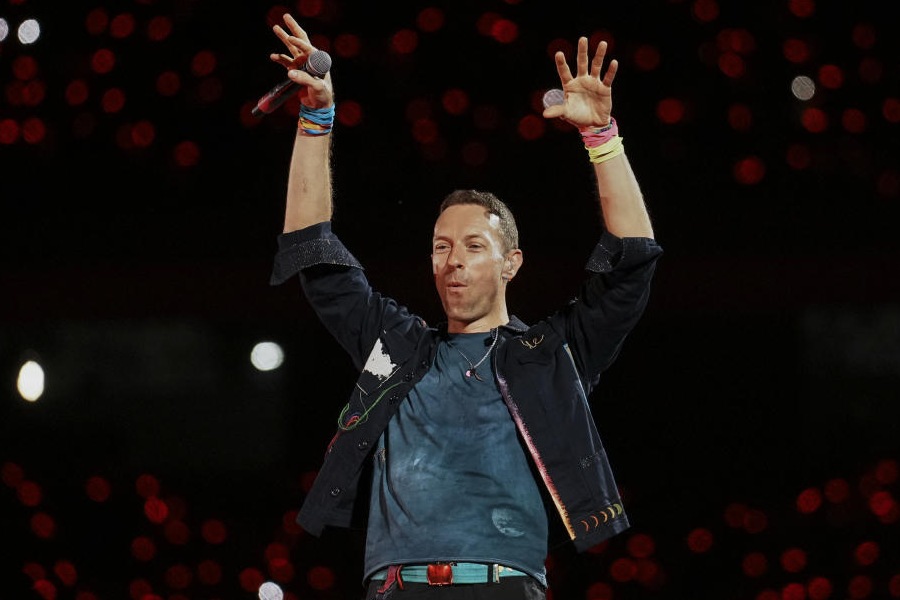

| Novel strategy: A children's book-reading session at Katha Publishing |

Vidur Butalia, an 11-year-old bookworm, knew about gravity much before his school textbook tried to teach it to him. He first got to know about Newton’s theory while reading a series called Horrible Science, a set of books for children. But Butalia was lucky. He grew up among books in a family that read.

Not everybody is as fortunate as Vidur. Teachers and parents hold that getting children to read is a tricky business. And lately, that is exactly what many publishing houses and bookstores are getting their heads and hands into. From storytelling sessions to zoo and nature walks, to play-acting and interactive activities — they are trying to get the young to read more. “A lecture from a pedestal didn’t work then and it doesn’t work now,” says Shobit Arya, publisher, Wisdom Tree, which publishes a huge range of books, from spirituality, to parenting and children’s books.

Storytelling has come a long way from a 15-minute bedtime reading of a Hans Christian Andersen fairytale. Now it is a group of schoolchildren sitting among hordes of cackling pelicans in the Delhi Zoo, while a fable of a weaver bird is read out to them. A walk through the birds’ enclosures in the Delhi Zoo before the reading has already whetted their appetite. And it is the migratory season. For the children, it is a double bonanza. Katha Publishing, which conducts these zoo walks-cum-storytelling sessions, is also tying up with the World Wildlife Fund to walk children through forests and grasslands, while reading from books. Rizio Yohannan Raj, managing editor, Katha Publishing, says that such activities not only encourage a child to browse the book but also spread a conservation message.

“An award-winning book doesn’t matter to a child. To them, reading is not a separate exercise. A link to their life and what they see is essential. It has to be active,” explains Raj.

Though story telling remains the classic way of introducing a child to books, experimentation is the key. Wisdom Tree, for instance, has an interactive programme which takes cartoonists, theatre actors, painters and other experts to schools to encourage children to explore a subject area of their interest through books. “We take along huge panels depicting books on these workshops. At a younger age, the look and feel of a book is more important. They like to hold it and see it,” says Arya. The children are pre-screened by the school and divided into groups of their interest, so that each student participates whole-heartedly.

Says Vatsala Kaul, commissioning editor, Puffin and Ladybird: “A child’s first reaction to a book is to eat it and then to approach it like a toy.” Both Penguin and Scholastics India, a global children’s media company, market their books to children through readings, book fairs and activities. Scholastics also promotes its catalogue through book clubs and newsletters in schools, which is a huge success. “The sales response to the newsletter is great,” agrees Sayoni Basu, editorial director, Scholastics.

Another bookstore, Eureka in Alaknanda, New Delhi, which caters only to children, invites them to treasure hunts. Children are given clues to certain books and they have to spot them in the store. “We also hold quizzes and debates for kids on reading topics, which are quite a hit,” says M. Venkatesh, co-owner of Eureka.

For the younger generation, the visual medium is far more appealing than the bland and sometimes intimidating medium of text. “A lot of schools encourage the Internet as a source of information. Children stop looking to books for information or entertainment,” says Kaul. So visual narratives and graphic books are a bigger hit. Katha, for instance, is creating new book covers which will provide a parallel visual narrative. “We are trying to merge the two disciplines of art and literature. We are planning an event in Mumbai soon, which will bring together illustrators, writers, translators and readers,” adds Raj. Katha hopes to create new readers through this venture, both young and adult.

In the glut and clutter of new media and stylised books, however, the quiet and reassuring voice of folktales has faded. Most of the last generation would fondly remember folk tales that have been passed down generations as an oral tradition. Some children’s book publishers are trying to preserve these very tales and fables by documenting them. “We have to mould the stories according to the modern child. So we tweak the narrative so that a folktale is not too old-world,” says Raj.

Though publishing houses’ strategies for book promotions have a two-fold agenda of encouraging reading and selling books, bookstores are focused more on sales. “We organise events and readings usually linked to a product and the prizes for contests are gift coupons, redeemable in our store. We have seen a 25-30 per cent rise in sales ever since we started these events,” adds Jitendra Jamwal, Crossword, Gurgaon.

Children get books and bookshops get customers. Though Crossword gives the children’s section just 10 per cent of its floor space, 40 per cent of revenue is generated through children’s books. Scholastics has also recorded a 30 per cent increase in sales annually.

Apart from sales, whether these innovative ways are actually helping the cause of making children read is anybody’s guess. “These strategies don’t get a direct response like 2,000 sms-es to KBC. It is still a nascent market, especially for Indian publishers. There is huge potential but the target audience is still not understood fully,” says Kaul.

On the other hand, Basu asserts that the Scholastics newsletter cum catalogue in schools provides children with much better access to books. “It is especially so for children whose parents don’t read much. They might take their children to a shop but they wouldn’t know what to buy. Also, compared to sales through bookstores, the Scholastics catalogue sells much more,” says Basu. That reading has its benefits goes without saying. Freakonomics, an international bestseller on everyday economics, mentions that children who grow up among books score much higher on tests than those who don’t. “But it isn’t that a child who picks up a fiction book will excel in academics. It is not a direct impact,” says Basu. “Reading adds to your lateral diversity. Such people make great conversationalists, are better at articulation and communication and have better discerning abilities,” explains Kaul. “A child who does not read does not see the wonder of the world. On a practical level, such children will tend to have weaker verbal and language skills, which impacts one’s professional competence,” adds Basu. Books, the editors hold, fuel curiosity, imagination and sensitivity.

As for Butalia, a book is all about learning and having fun at the same time — whether in school or outside. “They also make great gifts,” he adds perkily.