Mohamed Sadiq Shaikh's life has been one long dark tunnel ever since his son, Mohsin, was killed on the night of June 2, 2014 in Pune. The 20-something techie was caught in the middle of a communal flare-up over a social media post. Mohsin's killers allegedly belonged to an outfit called the Hindu Rashtra Sena (HRS).

Thereafter, the Shaikhs moved for getting justice for Mohsin in right earnest. Police made several arrests and the government of Maharashtra agreed to Sadiq's request that the case be handled by the well-known public prosecutor, Ujjwal Nikam. This was August 2014; the Congress-led Democratic Front was in power in the state.

But gloom descended on the Shaikh household after Nikam withdrew from the case this year without citing a reason. "He was successful in getting convictions in the Mumbai blasts case of 1993 and the Ajmal Kasab trial. We thought he would nail the culprits here as well. To this day I don't know why he resigned," says Sadiq, 63, who lives in Solapur in Maharashtra. The last text message Nikam sent Sadiq read: "Hope you will get justice. God is great."

About 200 kilometres west of Solapur, in Satara, Hamid Dabholkar is also waiting for justice. His father, the doctor-rationalist Narendra Dabholkar, was gunned down outside a temple in Pune in 2013. Around the time of his death, he had been lobbying for an anti-superstition legislation.

Dabholkar's killers are still on the run and the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which is looking into the case, hasn't been able to make much progress even on the one person who has been arrested. "Even the Bombay High Court, which is monitoring the probe, is frustrated with the pace of investigation," says Hamid.

In the last 10 years, about 120 people have been killed in bomb blasts in Malegaon (2006, 2008), Samjhauta Express (2007), Hyderabad Mecca Masjid (2007), Ajmer Dargah (2007) and Modasa (2008). All of them are believed to be the handiwork of Hindu extremist groups. But except for the Ajmer Dargah case, wherein two former Sangh activists were found guilty, no other case has recorded progress worth mention.

Some like Sadiq Shaikh claim there is a pattern in it. "You look across the country. If people have been killed in the name of hurting the sentiments of Hindus or simply for being a Muslim, as in my son's case, getting the guilty punished is nothing less than a miracle."

The National Investigation Agency (NIA) has taken over most of the cases involving suspected Hindutva outfits. "In my opinion, the NIA's main job has been to cover the tracks of the accused," says Vikash Narain Rai, former head of the special investigation team (SIT) set up by the Haryana government to look into the Samjhauta blasts. "It hasn't been successful in scuttling the Ajmer Dargah and Samjhauta blast cases, at least so far, because local police had done a great job," he adds.

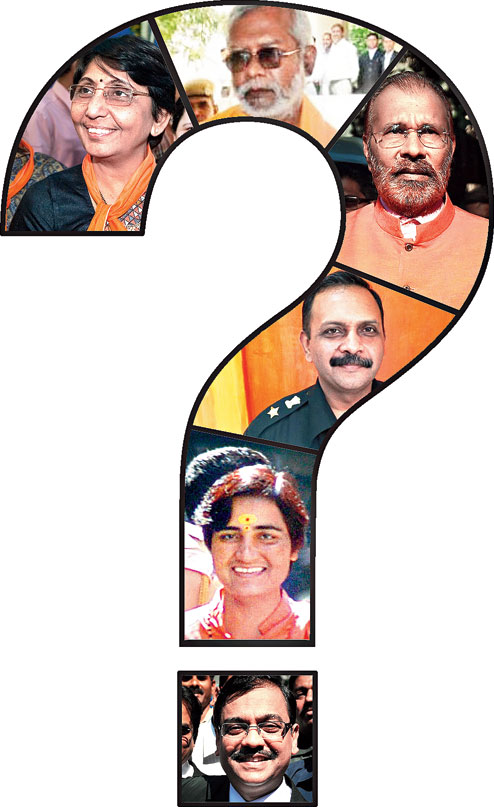

Rai says the Haryana SIT had enough evidence to prove that Swami Aseemanand and Sadhvi Pragya Thakur were involved in several bomb blasts. Both got away. The NIA, in fact, refused to challenge in the high court the bail granted to Aseemanand in the Mecca Masjid blast case. Rai points to the recent bail granted to Lt Col Shrikant Purohit, an accused in the 2008 Malegaon blast case. Purohit, who was in jail for nine years, was granted bail by the Supreme Court after he argued that he was serving as an army mole and was in no way involved in any terrorist activity. Purohit is back in uniform now.

"His bail was celebrated as if he had been declared innocent by the Supreme Court. The Military Intelligence was in the loop about his activities and Hemant Karkare as head of the Maharashtra Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS) had done a fantastic job. Now the NIA and others are in the process of undermining everything."

Rohini Salian, the former public prosecutor in the Malegaon blast case, had also alleged that the NIA had asked her to "go slow". She says, "Not only the Malegaon blasts, in other cases too, the Maharashtra ATS had done a great job. But the NIA contradicted the ATS on several points and these were done to weaken the prosecution argument. They may not do it directly, but they will deliberately leave enough loopholes."

Even in the Ajmer blast case, public prosecutor Ashwini Sharma had complained that many more would have been found guilty had the NIA been more thorough. The Ajmer blast litigation had reached such a state that prosecution witnesses were seen being tutored by defence lawyers. Not surprisingly, many turned hostile. Neither the CBI, nor the NIA responded to The Telegraph's queries.

That there is pressure it is obvious, though no one is quite willing to elaborate on it. Some social activists in Pune believe that Hindutva organisations persuaded public prosecutor Nikam to resign from the Mohsin Shaikh case. Azhar Tamboli, member of the Pune-based Maharashtra Action Committee, an NGO working for minorities, says, "We don't know this for sure but there can't be any other reason as Nikam was doing a great job. Many like me feel this is one case in which he may not have been treated like a hero had he won here, and he didn't want to lose either."

Nikam told The Telegraph he mentioned his reasons to chief minister Devendra Fadnavis. "I can't reveal the reason, but I did it in the larger interest." He rubbished all talk of being pressurised.

There are others who are more forthright about their choices. Advocate Sanjiv Punalekar only jumps to the aid of any Hindu being "victimised" by police. Punalekar is the advocate for many of the accused in the Mohsin Shaikh case - including the main accused Dhananjay Desai - as well as the Dabholkar case. He also represents Sanatan Sanstha, which is suspected of being involved in the killing of rationalists Dabholkar, Govind Pansare and M.M. Kalburgi. The Sanstha has also defended some of the accused in the Malegaon blast case and the former Gujarat police officer, D.G. Vanzara, an accused in the alleged fake encounter of Sohrabuddin Shaikh.

In August this year, a special CBI court in Mumbai discharged Vanzara citing lack of evidence.

Another set of people, from among victims' kin and activists, says this case of grossly impeded justice is common to all parties in power. Says Dabholkar's son Hamid, "My father was killed when the Congress was ruling [in Maharashtra]. But it didn't show the inclination to go after the Hindutva organisations."

Former SIT boss Vikash Narain Rai says that the central government led by Manmohan Singh didn't seem keen to go after Right-wing Hindutva groups even after it was "proved beyond doubt" that they were involved in various bomb blasts.

Rohini Salian had given her consent to becoming the public prosecutor in the Mohsin Shaikh case but was not accepted by the Fadnavis government. She says, "I feel very sad, looking at the way cases are turned on their heads by the prosecution, disregarding the victims and the truth. Only God can save this country."

Everyone finds someone to blame. Nikam contends that more often than not it is the police who weaken their own case. Suddenly he is open to talking about "pressures" and being pressurised. "Because of political or media pressure, they don't probe well and accuse as many people as they can and arrest many innocent people in the process," he says.

Nirjhari Sinha is the founder of a Gujarat-based non-profit group, Jan Sangharsh Manch, which has filed several petitions relating to fake encounters and riots. According to Sinha, emboldening those accused of violence and murder and sending a signal to everybody down the line is yet another practice that has been adopted in recent times to confound justice.

Citing the recent appearance of BJP president Amit Shah as a defence witness in a 2002 post-Godhra riots case, in which former Gujarat minister Maya Kodnani is an accused, she says, "The high courts and the Supreme Court have often come to the aid of the victims. But the CBI and state police have found ways to slow down investigations."

She talks about the alleged fake encounter case of Sohrabuddin Shaikh in 2005, in which most of the indicted, including the top-rung of Gujarat Police were acquitted by a lower court and the CBI refused to appeal. The Bombay High Court recently pulled up the CBI asking it why it didn't appeal against the lower court's ruling. Says Sinha, "The CBI obviously has been instructed not to pursue the case in higher courts."

A sense of disquiet is palpable when Irshad Khan speaks up. His father Pehlu Khan, a dairy farmer, was killed by gau rakshaks at Alwar in April. He was transporting cows for his small dairy farm. Irshad's question, "My family is losing hope every day. The people my father named before dying have been declared innocent by the police. Others are on bail. The whole world saw how my father was killed. What more evidence do they need."

Azhar Tamboli, member of the Pune-based Maharashtra Action Committee, says the victims have been abandoned. "What makes it worse now is that the state is now siding with the perpetrators through its various acts of omission and commission. We can only fight back. Whether we will get justice for the victims is a different matter. Fighting is the only thing we can do."