On November 20, 2016, I was in a village in Hooghly district with other volunteers of our small non-governmental organization, waiting to interview applicants for one of our training programmes. We were in a samabay krishi unnayan samiti (a cooperative society set up, as the name suggests, for the benefit of farmers) at the invitation of the samiti’s members, who wanted us to conduct one of our courses there. Usually, these interviews are congenial, even jolly, affairs, with a lot of banter and crosstalk; occasionally, we would encounter someone who was clearly unfitted for our course (usually by virtue of belonging to a higher income group than our targeted beneficiaries) and sometimes there were far too many applicants than we could possibly accommodate; but this time there were just 28 applicants for 20-odd places in our course, so it should have been smooth sailing. Except that it wasn’t. An air of gloom, even desperation, seemed to hang over the proceedings; applicant after applicant spoke of the dire uncertainty of their future, not just in economic terms but in ways that embraced pretty much all aspects of their lives — the impossibility of being certain if a daughter would be able to go to college, a nephew get married, a chronically ill parent receive treatment, a close relative get a loan to set up a small shop, and so on and on and on.

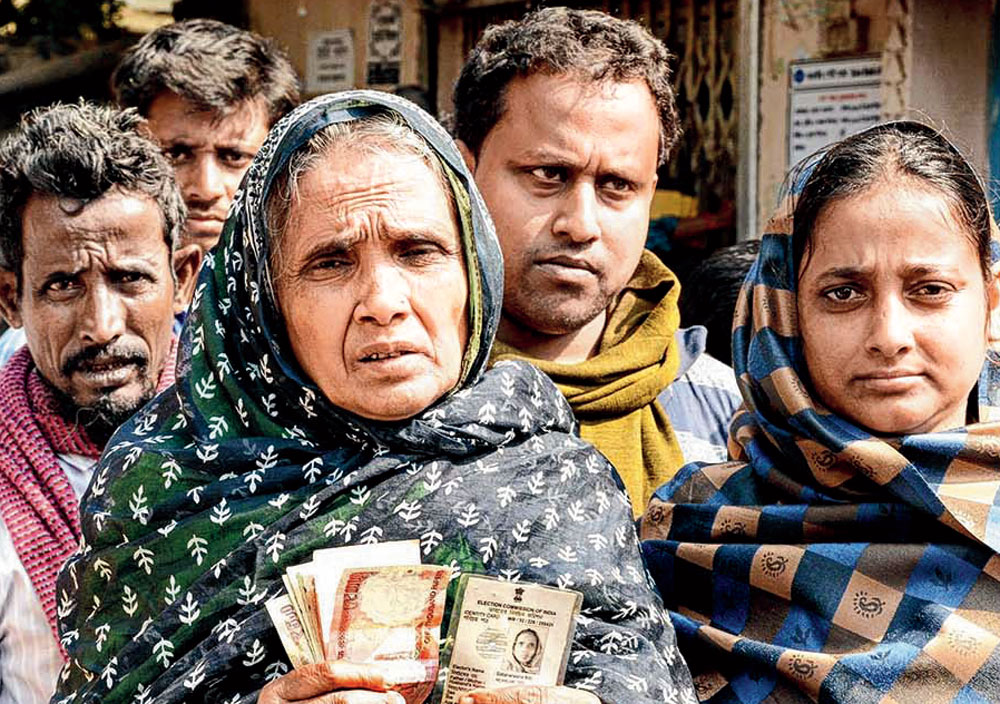

Somewhat surprised to begin with, we were soon struck by the realization that it was less than a fortnight since the historic announcement of demonetization on November 8 2016, and just six days since the notification by the Reserve Bank of India that district central cooperative banks would no longer be allowed to accept deposits or exchange the now worthless 500- and 1,000-rupee notes. Virtually everyone we met that day had the bulk of her or his savings in cooperative societies which, in turn, did the bulk of their business with DCCBs. In the few days that DCCBs had accepted deposits and exchanged currency notes from SKUSs, transactions worth hundreds of crores had already taken place. Although people had had to stand in line for hours, most SKUSs had risen to the occasion and increased their work hours and the number of people at their counters. But now, it was all over. Not a single one of the people we met that day — the applicants for our course, family and friends who had accompanied them, members of the SKUS, other folk from the village — had any idea of how, if ever, this nightmare would end. This was the miasma of gloom and fear that hung over the meeting room that cool November afternoon 25 months ago. Things didn’t really change much in the following weeks and months and a year later they were still limping along at best, as samiti members kept telling us. It was not until next year, and after much litigation, that DCCBs were finally allowed to deposit the demonetized notes in their vaults with the RBI.

These memories swum to the surface as I read Meera H. Sanyal’s The Big Reverse: How Demonetization Knocked India Out — an account of the devastating effects of demonetization on the times and lives of hundreds of millions of ordinary Indians. Sanyal is one of India’s most successful bankers, someone who has served in top positions in some of the world’s largest banks and financial institutions. She is no air-headed socialist; on the contrary, she champions markets, competition, and the need to encourage entrepreneurship, small-scale and large. Like most of us, she believes the stated aims of demonetization, as announced by the country’s prime minister on the night of November 8, 2016 — eradicating black money, ending corruption and stopping terror-funding — are eminently laudable objectives that no patriotic Indian ought to argue with. To these three primary goals, she adds five others announced by the government’s spokespersons in the days following demonetization: moving to a cashless society, expanding the tax base, integrating the informal sector of the economy with the formal, lowering interest rates and bringing down real estate prices. In the sixth chapter, “Demonetization Report Card”, she draws on government statistics to show how not a single one of these eight objectives came even close to being achieved. In her other five chapters, not including the Introduction and Conclusion, Sanyal looks at the effects of demonetization from the angle of people, institutions, economics and history. And what she says does not make for pretty reading.

I am no economist or political scientist, but in over three decades of trying to understand literary texts, and by speaking with people from a wide range of backgrounds, I have understood two things: stories matter and memory is short. For most salaried city-dwellers like me, demonetization was a shock to the system, but a shock we recovered from fairly rapidly. In the days immediately after November 8, 2016 many (most?) neighbourhood shops opened khatas for their regular customers, where purchases were noted down and payment asked for only after the total had inched close to Rs 2,000; more establishments started accepting card payments; even queueing up outside banks and ATMs turned into something resembling a street-side adda, and the frequent (and often contradictory) orders issued by the RBI provided much grist for the mills of para humorists. Yes, there was hardship, which we encountered not always first-hand but often from those who worked in our homes or ferried fresh provisions to our doorstep or ran a local chai shop; and many times we helped them out in small but not insignificant ways — by not asking for change, by taking their now-useless notes and giving them fresh legal tender in exchange, by making advances against a future month’s salary, and so forth. Things were far worse in non-urban areas. There is little data on how many people lost livelihoods in villages, how many patients went untreated, how much additional interest had to be given to usurious moneylenders to pay for daily necessities, how many social gatherings and family events had to be cancelled or drastically curtailed… yet anyone who has even a nodding acquaintance with rural India will have heard many of these stories of loss and despair.

On the 21st day of the second month in the third year after demonetization most of those who read this paper will have probably forgotten the hardships undergone by ordinary people, the chaos created in every sector of the economy, and the failures swept quietly under the carpet by the architects of demonetization. Through her meticulously documented, carefully crafted, deeply felt and, most of all, profoundly human book, Sanyal has given us reason to remember the many stories that went into the making of this strange and, ultimately, tragic chapter in our country’s recent history.

The author is professor of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, and has been working as a volunteer for a rural development NGO for the last 30 years