During the winter months at the end (and beginning) of the year, while the air in the city carries the aroma of freshly baked cakes from bakeries, in the villages of West Bengal, it is time to celebrate the new harvest. Rural Bengal is rich with the scent of pithe-puli — a traditional Bengali sweet made with newly harvested rice, milk and nolen gur. The Bengali month of Poush, which spans parts of the Gregorian months of December and January, is the time for homemade savouries and sweets made from new rice, or naba anna. The celebrations are not restricted to the villages though, it has reached Kolkata and from there gone to other parts of the globe and various events centred around Poush Utsav are organised throughout Bengal.

One of the main features of the festivities is the making of ‘pithe’ and ‘pithe puli’ with the newly harvested rice, milk, coconut and season’s special — nolen gur Wikimedia Commons

Poush is the month for delicious food like pithe-puli, patisapta, soru-chakli and the month for Poush Parbon or Poush Utsav, when everyone participates in the month-long celebration of making these treats, that ends with Poush Sankranti, the last day of the Poush month. In reality though, Poush Sankranti is the last day of the two-month celebration that starts from the first day of the month of Aghrayan that precedes Poush in the Bengali calendar.

Celebrating a new harvest

A payesh made with the newly harvested rice along with the grain itself is offered to god and kept in auspicious locations in the house, like the kitchen tourismwb/Facebook

Bengal’s Burdwan has been historically known as the granary of Bengal because of the paddy harvest of the district. Today, in East Burdwan, and the adjoining districts of Birbhum, Murshidabad, Hooghly, Nadia and West Burdwan, the festival begins from Aghrayan itself and the new harvest is rejoiced for two months.

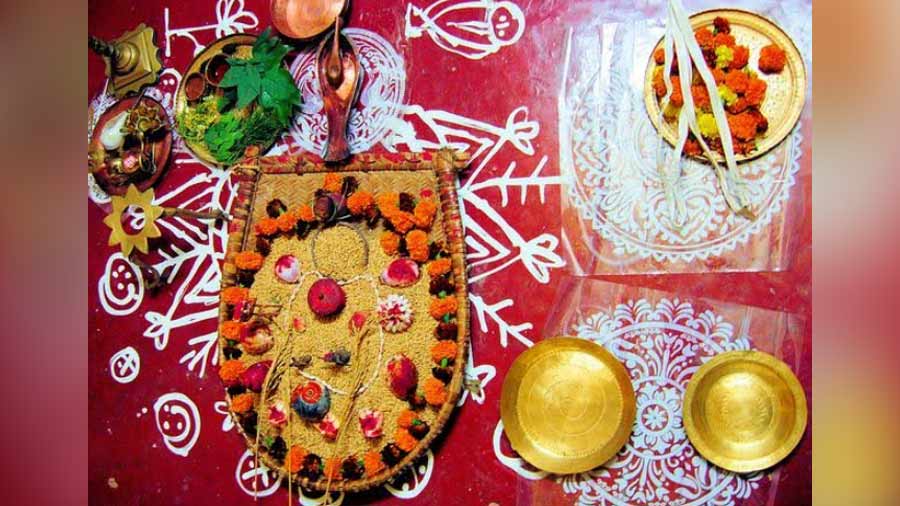

A portion of the first lot of newly harvested aman paddy — the variety of rice that is grown in this season — is put under a pedal press for husking. On an auspicious day, this rice grain is powdered through using a mortar and pestle and a payesh (or kheer) is made with the rice powder, milk, and coconut. Along with the payesh, some sandesh, fruits and khejur gur or nolen gur is arranged as an offering known as Nabanna. The payesh is offered to the deity at home, and also served on a banana leaf and kept in the cowshed, the kitchen and other auspicious places of the household.

Festive memories

The ‘Nabanna’ offering includes sandesh made with ‘notun gur’ or ‘nolen gur’ Wikimedia Commons

Septuagenarian Shikha Das, who is from Kandi in Murshidabad, recalls her childhood days, when the household festival didn’t end with preparing the Nabanna only, and pithe-puli used to be made from the remaining portion of the ground rice and distributed among neighbours and friends. This was followed by a sumptuous meal at home with a variety of bhaja, dishes cooked with seasonal vegetables and finished with the freshly made pithe-puli.

The celebration of the newly harvested paddy didn’t end on a single day. It was followed by Baas Laban or Bashi Nabanna, where the naba anna was not fresh, but a day or days older. The next day of Nabanna used to be a celebration not for the household but the farmers. The festive menu usually featured a meat preparation, rice and local liquor made from dates. The new harvest was celebrated for a few days with each para hosting the feast in turns and the one with the best festivities was rewarded on this day — similar to celebrations on the last day of the month of Bhadra.

‘Nabanna’ festivities sometimes continue the next day with a feast of meat, rice and liquor made from dates Wikimedia Commons

Celebrations today

When is Nabanna or Laban celebrated? There is no fixed day for Laban (as it is called in central Bengal). The entire district of Burdwan used to celebrate only after Nabanna was offered to Devi Sarbamangala, following a custom started by Maharaja Tej Chand of Burdwan. However, with time, the practice has altered with the increasing population of the area. While Katwa celebrates on the day the Nabanna is offered to the local Khepi Ma and Chaitanya Bari, Kalna celebrates on the day the offerings go to the Siddheswari Kalibari and Lalji Mandir. This also makes Nabanna an event to celebrate irrespective of being a Vaishnav or Shakta follower. In Kandi, Murshidabad, the celebrations don’t depend on the temple offerings but the erstwhile zamindars of the region — the day the Lala Babu family celebrates is the day of Nabanna for the entire block.

The Sarbamangala temple in Burdwan Rangan Datta

The pattern of celebration has also changed with time. The entire village does not celebrate on the same day anymore and it depends on many factors, including political allegiance. In larger villages, Nabanna is celebrated on different days in different parts.

Sixty-year-old school teacher Tushar Pandit from Katwa laments that Nabanna is no longer the festival of baansh-Kartik — a festival which used to be celebrated by venerating Kartik as the main deity. The jatra, kobi gaan, taarja of older years has been eclipsed by the DJs of modern times and that is where the present generation feels comfortable. Kalna resident Mishtu Chatterjee doesn’t know when the Nabanna is to be celebrated, she only knows that it is to be celebrated and accordingly, she gathers her enthusiasm to ensure she is among the first few in the queue on the day when the offering is given to the deity.

An important and beautiful part of Nabanna is the fact that on the day, the celebrations are spread across Hindu and Muslim families. In this regard, the communities in the villages have always been in harmony without any discord for centuries.

The feasting continues

‘Chitoi pithe’ and (right) ‘soru-chakli pithe’ often feature in the feasts for Poush Sankranti Wikimedia Commons

Poush Sankranti is still celebrated today with chitoi pithe, pithe-puli, pakkan pitha as they used to be in yesteryears. The elo-jhelo pithe and shora pithe have been lost in oblivion just like moog sambli made from moong dal. The days of the button-sized pithe for Itu Sankranti, as Poush Sankranti is also called, may have disappeared with time but with the north winds, the aroma of freshly made pithe flavoured with nolen gur still hits us towards middle of January as the two-month harvest festival comes to an end.