And then he was shot in the neck.

Did he survive?

Let’s just say his story has survived. As an intriguing tale that still takes one back to that full-moon night of passion and fury. A night full of strange images, of a heaving, swollen river, and a pale, white young man the watchman saw lying inside a carriage, limp hand dangling from the door.

What else did he see?

A trail of blood.

Fresh blood?

As fresh as 200 years old. Spilled in a duel on the sprawling grounds of the home of one of the most powerful men in Bengal then.

Belvedere House it was called — and the man who lived there was Warren Hastings, the first governor of the Presidency of Fort William (Bengal). In fact, it was Hastings who had fired the bullet.

That would be sometime in the 1780s. Today, nearly two centuries and a half later, the sprawling estate is home to the National Library, a grand imposing landmark on the city’s intellectual map.

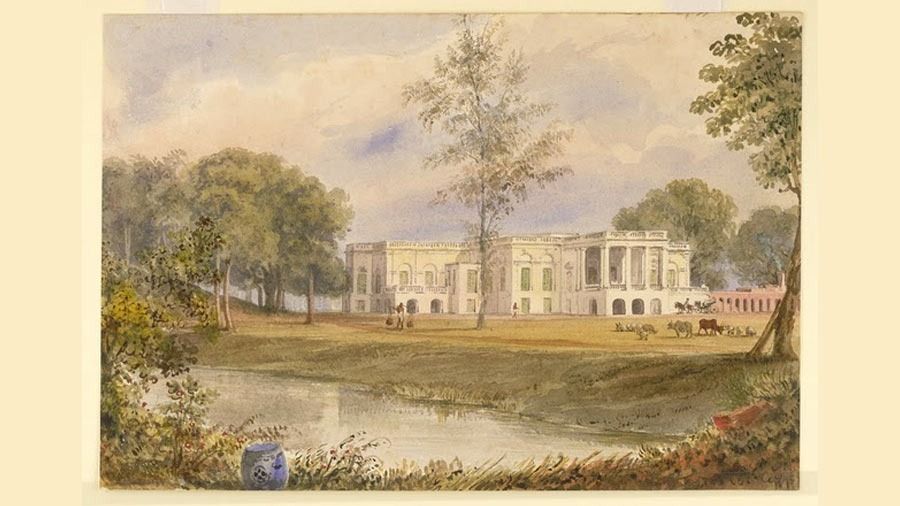

A painting of Belvedere House

Who would have thought that the two and a half million books the campus is home to had such a bloodstained past? It’s of course an indirect link, at best a tangential connection, because Hastings was dead by the time the library was originally established in 1836, when it was known as Calcutta Public Library, but history thrives through associations.

That’s how the story of the duel has lived on too — its longevity amplified by phantom images that still play on the mind. Images of two men, looking each other in the eye, their mutual animosity no more in need of any pretence of civility. They turn away, walk a few steps and then suddenly turn around again, pistols drawn, aimed at the other. And then the sound of gunfire.

Warren Hastings

Where silence whispers in the middle of chaos

It’s hard to imagine that gunfire had once shattered the silence of these grounds in Kolkata’s Alipore area. But then, one of the curious things about cities with a history is that one can nearly always find pockets where silence whispers in the middle of chaos. Kolkata’s National Library is one such space. On the south bank of the Ganga, as you step off the crowded streets and cross the huge iron gate, it feels as if time has travelled a few paces backwards into a hinterland of memories, the bustle and throb of the world outside muffled by the rows of trees on the library’s sprawling campus.

The library building has since shifted, from the 230-year-old mansion and two annexe buildings to the plush Bhasha Bhavan on the same Alipore campus. But veterans, who were regular visitors to the old building, still remember the ambience; the odour of words that would hang heavy in the air, the whirr of old ceiling fans broken only by the rustle of pages or the sudden thud of a book on the table. Between the huge bookshelves stretched long, empty corridors, like liminal spaces between a public front and a private secret.

By the time the library closed for the day, it would be dark, and the last person to leave the immense halls would often turn around wondering if they had heard a sound from a different time.

Has he ever heard such sounds?

Beerbahadur, a watchman on the campus, shakes his head. But he had seen something stranger. And it had chilled him to his bones. But first, a brief recap.

A beautiful begum gets what she wished

It was sometime after the Battle of Plassey, 1757. Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah was dead and his former commander, Mir Jafar, was a resident of Belvedere Estate, dependent on the British East India Company for his survival. With the nawab, then already in his late sixties, lived his young and beautiful wife, Munni Begum.

Bengal was under the jurisdiction of the East India Company and Hastings, a powerful figure in the administration, would eventually come close to the nawab and his family.

Hastings didn’t need long to figure out the gaps in the nawab’s personal life as he became a frequent visitor to the estate. One day, Munni Begum came up with a request. She wanted a mahal (living quarters) of her own, a personal space where she could say her prayers and enjoy her privacy. The wish was soon granted and Hastings, it appears, would often visit the begum in what came to be known as her Khaas Mahal.

Mir Jafar remained unaware of this friendship. Then one day he paid his wife a surprise visit and found her with the future governor-general. But such were the circumstances that the nawab was powerless to do anything. Eventually, he would hand over the whole estate to Hastings and leave.

A baroness, and the story behind the story

But the grounds of the estate had not been bloodied yet. That would happen a few years after Hastings became governor-general in 1773.

Four years earlier, in 1769, Hastings, then a widower, had met the German baroness, Marian Von Imhoff, and her husband. He fell in love with the baroness and the two began an affair, apparently with the consent of Marian’s husband.

But Hastings was a busy man and his legal officer, Philip Francis, took advantage of the governor-general’s schedule. He started visiting the baroness in her room.

Hastings was furious and challenged Francis to a duel. Then, one December night, pistols loaded, they faced each other on the western grounds of what was then known as ‘Hastings House’.

Hastings appears to have been quicker on the draw and Francis slumped to the ground, shot in the neck. Hastings and others present at the scene rushed to help the fallen man. The governor-general even arranged for a palki (palanquin) to take the injured Francis to hospital. What happened after that is hazy. Apparently, when the palanquin bearers reached the banks of the old Ganga (Adi Ganga) on that full-moon night, they found the tide was high. It’s possible that Francis bled to death inside the palanquin. Other accounts of the duel say Francis survived, but that has little bearing on this story. What is fascinating about the incident is the story behind the story and the vivid images it conjures up; heard memories recreated and imagined as real in sudden unguarded moments.

Watchman’s vision on a full-moon night

So, two centuries later, on a full moon night, when watchman Beerbahadur was on duty on the western lawn inside the National Library campus, he would see a palanquin cross the grounds. Inside the carriage lay a white young man. Blood dripped from his hand, leaving a trail of red on the pale moonlit lawn, before the spectral palanquin melted into the luminous night. Sometimes, the ambiguities of outcome are more captivating than the prosaic certainty of details.

Much has changed since the day blood stained the grounds of the estate, the series of names itself a mirror to the evolving history of the state. If it was a neutral Belvedere Estate when Mir Jafar was the nawab, his exit meant the end of the building’s nawabi aura. Before long, the building would come to be known as Hastings House. The British, needless to say, were well on their way to establishing their dominance in India.

In 1948, the building would be renamed National Library, the change of name from Imperial Library — as Calcutta Public Library had been rechristened — reflecting the altered status of a newly independent nation.

The National Library as it is today

What has not changed is the invisible feel of history, the rustle of the past that lingers in every corner. Some old visitors to the library have even claimed that, deep in study, they would look up startled, their concentration broken by the sound of a few pairs of legs shuffling under a weight and a rhythmic hum, but seen nothing.

Tricks of time? Who knows. Or maybe, like the spirit of the injured Francis, the spirits of the palanquin bearers too had preferred the lasting invisibility of the intangible world to the ephemeral visibility of life.