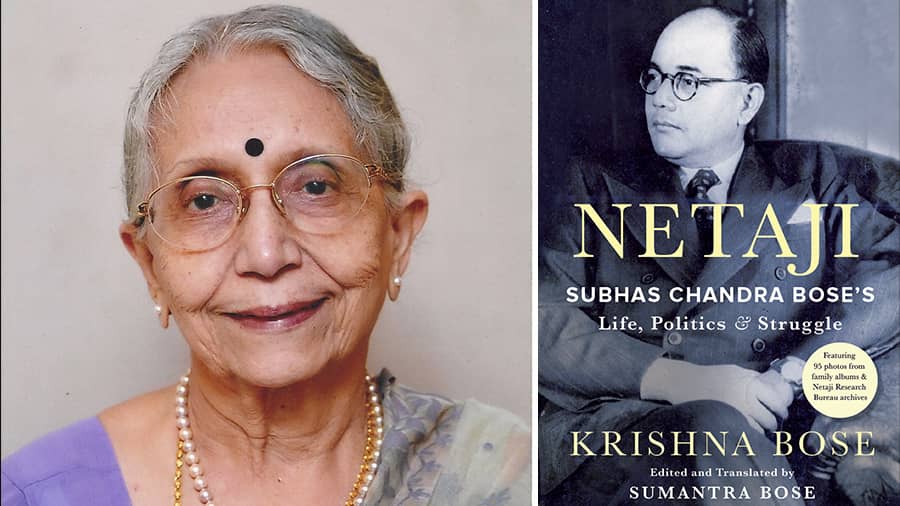

Netaji’s personal and political life, his relationship with other freedom fighters and his death — 18 essays by Krishna Bose written over four decades have been compiled into a single book, Netaji: Subhas Chandra Bose’s Life, Politics & Struggle.

The essays, most of them originally written in Bengali, were published in prominent newspapers and magazines. Sumantra Bose has translated the essays into English.

Sumantra Bose has translated the Bengali essays into English

My Kolkata shares an excerpt from the book:

When we look back at our struggle for independence, one is struck by the galaxy of outstanding leaders India produced during the first half of the twentieth century. It rarely happens in history that a nation produces around the same time leaders of the calibre of Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose.

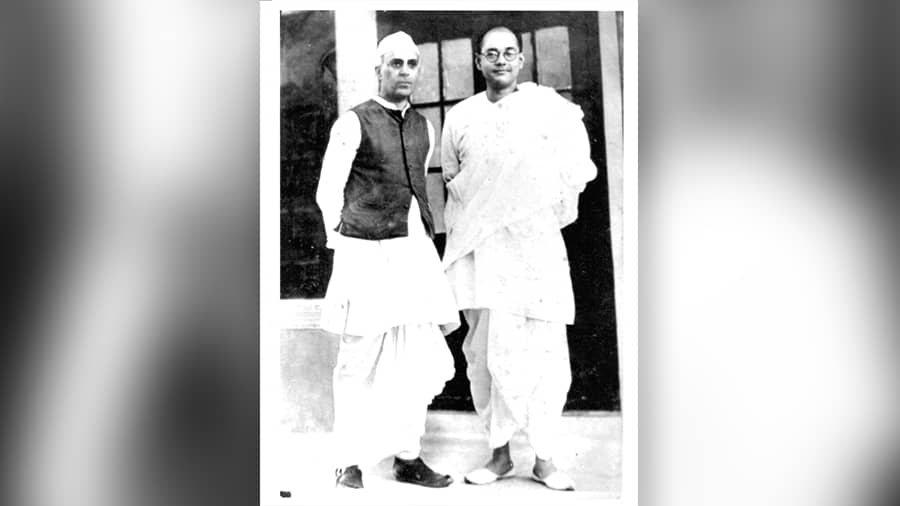

Of all the brilliant leaders of that era, a comparison of Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose is the most fascinating because it reveals certain similarities but at the same time basic dissimilarities between the two men. It’s intriguing to speculate what would have happened if the two had been able to chalk out a common programme and India had been served at once by her two great sons.

Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose

But that was not to be. By 1939, a deep divide separated the two men. In April 1939, after the contentious and personally traumatic Tripuri session of the Indian National Congress, Bose wrote with manifest bitterness – ‘Nobody has done more harm to me personally and to our cause in this crisis than Pandit Nehru.’ And during the war, when rumours reached India that Bose was coming with the victorious Japanese, Nehru declared that he would be the first person to meet him with a drawn sword.

When Bose and Nehru first appeared on India’s political scene in the early 1920s, they appeared alike in many ways. Both emerged as leaders of youth and both had a magnetic charm about them. No other leaders of the time possessed this youthful charm which cast a spell on the nationalist masses.

A glimpse into their growing-up years, however, reveals major differences. Both were born into well-to-do families. But Subhas turned his back on the life of comfort and chose to embrace a self-imposed austerity when he was a stripling of fifteen. The letters he wrote to his mother Prabhabati and his older brother Sarat Chandra Bose even at that age reveal how his mind was tormented by the country’s sorrowful plight. ‘Will the condition of our country continue to go from bad to worse – will not any son of Mother India in distress, in total disregard of his selfish interests, dedicate his whole life to the cause of the Mother?’ he wrote to his mother in 1912, aged fifteen. To his school friend Hemanta Sarkar he wrote: ‘My life is not for enjoyment, my life is a mission.’ During Bose’s time in Cambridge, his friend Dilip Kumar Roy says, he considered it a waste of time to read a novel or go to the theatre. He had a sense of urgency, of preparing for his life’s mission.

For the young Nehru, thoughtful and imaginative as he was, there was no such sense of mission. Had Nehru not met Gandhi when he did, his life may have remained as it was. It was in 1920, when he was already into his thirties, that Nehru had an accidental meeting with a group of kisans (peasants) and suddenly became aware of the acute misery of the vast majority of his fellow Indians. He was deeply moved by the experience. He wrote: ‘A new picture of India seemed to rise before me, naked, starving, crushed and utterly miserable.’

The first influence on Nehru outside of his own family was his Irish tutor, F. T. Brooks. For Bose, it was the Bengali headmaster of his school in Cuttack (Odisha), Beni Madhab Das, who impressed upon him the importance of moral values. The next important event in Nehru’s life was his schooling in England, as a bright Indian boy with an interest in current affairs studying at the Harrow School. For Bose, who was seven years younger, the landmark event at the same age was becoming acquainted with the works of Swami Vivekananda:

‘My headmaster had roused my aesthetic and moral sense – had given new impetus to my life – but he had not given me an ideal to which I could give my whole being. That Vivekananda gave me.’

The young Subhas went through a personal revolution of sorts when Vivekananda entered his life. The service of humanity that is your own salvation became his life’s goal. At sixteen, he temporarily left home in search of a guru. Throughout his student years, Bose practiced ‘Brahmacharya’ and led a life of austerity amid his family’s relative affluence. By contrast, Nehru writes in his autobiography that while in England he had the lifestyle of ‘a man about town’ and often exceeded the handsome allowance his father sent him from India. While at Cambridge, he ‘enjoyed life and refused to see why I should consider it a thing of sin’. The contrast of the formative years of Nehru and Bose is truly striking.

Another note of comparison should be made here. That is regarding their attitude to religion. ‘Of religion I had very hazy notions,’ Nehru wrote, and he remained an agnostic all his life. Bose did not care much for the ritualistic aspects of religion but he remained a deeply religious person in the broadest, most catholic sense of the term, all his life. Even during the frenetic time of the Azad Hind movement in Southeast Asia during World War II, his colleague S. A. Ayer has recorded, he would retire to meditate and emerge with fresh energy. Bose drew immense strength from his personal version of faith. It was for him, as he himself put it, a pragmatic necessity.

At the beginning of their political careers, the two strikingly handsome young leaders seemed to have a good deal in common. Their modernist orientation in politics and economics distinguished them from the deep-dyed Gandhians. Nehru and Bose shared a scientific approach towards India’s problems that was fundamentally opposed to the Gandhian creed of spinning our way to Swaraj and theories of non-industrialization. But while Subhas would openly profess his views, Nehru was forever wavering between his loyalty to Gandhi and his own convictions.

Bose set up the National Planning Committee – the forerunner of post-independence India’s Planning Commission – when he became Congress president in 1938. He asked Nehru to be its chairman. He wrote to Nehru: ‘I hope you will accept the chairmanship of the Planning Committee. You must if it is to be a success.’

Gandhi did not think much of the committee. But Nehru accepted the position regardless. Rabindranath Tagore, then in his final years, was very keen that the National Planning Committee should function effectively. In November 1938, as the Gandhi–Bose confrontation loomed, Tagore wanted a ‘modernist’ as Congress president. Tagore’s secretary Anil Chanda wrote to Nehru: ‘In his [Tagore’s] opinion and in the opinion of us all too, there are only two genuine modernists in the High Command – you and Subhas Babu. Your active cooperation is already secured by your being the chairman of the Planning Committee and he [Tagore] therefore is very eager to see Subhas Babu again elected the President.’

Subhas Chandra Bose as Congress president at Haripura, Gujarat, 1938, with Rajendra Prasad, Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Patel and Pandit Nehru. Maulana Azad has his back to the camera at far right

There was one other important field in which Nehru and Bose shared an interest: international affairs. That was unlike other Congress leaders, including Gandhi, who, when abroad, spent more time preaching principles of non-violence and the virtues of vegetarianism than in making India’s case for freedom. Both Nehru and Bose travelled extensively in Europe and helped to win friends there for India’s cause. But beyond this, they differed in their approach to India’s foreign relations. Broadly speaking, Nehru tended to idealism and Bose to realism. Nehru was revolted by Nazism and the persecution of Europe’s Jews. Bose on the other hand felt that the Indian struggle for freedom should override all other considerations. Thus, he stated: ‘In connection with our foreign policy, the first suggestion that I have to make is we should not be influenced by the internal politics of any country or the form of its state. We shall find, in every country, men and women who will sympathize with India’s freedom, no matter what their own political views may be.’

Jawaharlal Nehru was not just independent India’s prime minister but also its foreign minister for nearly seventeen years, from August 1947 to May 1964. History is yet to properly judge his record on that front. Subhas Chandra Bose headed the Provisional Government of Free India – Arzi Hukumat-e Azad Hind, proclaimed in Singapore on 21 October 1943 – for less than two years. During that time, he showed remarkable boldness in dealing with powerful and ruthless men. As a representative of a colonized nation, he held his own against men like Japan’s Tojo and earlier Hitler, whom he pulled up in their only meeting on 29 May 1942 for writing derogatory things about Indians and expressing open admiration for the British Empire. M. R. Vyas, who was a close associate of Bose in wartime Berlin, writes: ‘In Netaji’s actions I could perceive the truth of the political axiom generally attributed to Marshal Stalin; namely, that a good foreign minister is worth ten armies.’

The basic difference between the two men is summed up in one remark in a letter of Nehru to Bose. This was in Nehru’s reply to a letter Bose had written him in twenty-seven typed sheets. Bose had written: ‘I have looked upon you as politically an elder brother and leader and often sought your advice.’ The sentiment was appreciated by Nehru, who wrote back: ‘I am grateful to you for this. Personally I have always had, and still have regard and affection for you though sometimes I did not like at all what you did or how you did it.’ Why so? According to Nehru: ‘To some extent, I suppose, we are temperamentally different and our approach to life and its problems is not the same.’

Besides the difference in temperament, one other factor came between the two men: Mahatma Gandhi. Nehru had a practically unconditional allegiance to Gandhi and Gandhi exercised a hypnotic power over him. But Bose, whilst deeply respectful of Gandhi, was not as mesmerized. Like Bose, Nehru did not agree with Gandhi on many matters big and small. But whenever a dilemma or crisis arose, he surrendered to Gandhi’s will. Gandhi too showed great patience with Nehru in disagreement. On one such occasion, Gandhi wrote to a fretting Nehru: ‘Resist me always when my suggestion does not appeal to your head or heart. I shall not love you the less for that resistance.’ Gandhi did not show Bose the same affectionate consideration, above all in 1939, after Bose was re-elected to the Congress presidency against Gandhi’s wishes and candidate in a democratic vote.

Bose knew very well Nehru’s subservience to Gandhi and did not grudge it. Indeed, he wanted to leverage Nehru’s unique relationship with Gandhi. Bose wrote to Nehru in 1936: ‘Among the front-rank leaders of today you are the only one who we can look up to for leading the Congress in a progressive direction. Moreover, your position is unique and I think that even Mahatma Gandhi will be more accommodating towards you than towards anybody else.’ A Bose–Nehru ‘progressive’ alliance remains one of the most intriguing counterfactual scenarios of India’s history. But it could be that Nehru regarded the younger man not so much as a potential ally but as a potential rival to India’s post-Gandhi leadership.

The ultimate destinies of the two men were very different, and so is their place in Indian, Asian and world history. Jawaharlal Nehru is chiefly remembered today for his seventeen years in power in post-colonial India. Subhas Chandra Bose, on the other hand, lives in history and in the collective memory of the Indian people as the leader who challenged colonial power.