Where do feelings originate in life? Or, if the question can be rephrased: why do feelings happen, or seem to happen, in the inner mental worlds of humans and other creatures, especially when we are not looking for them? Do bacteria “feel”?

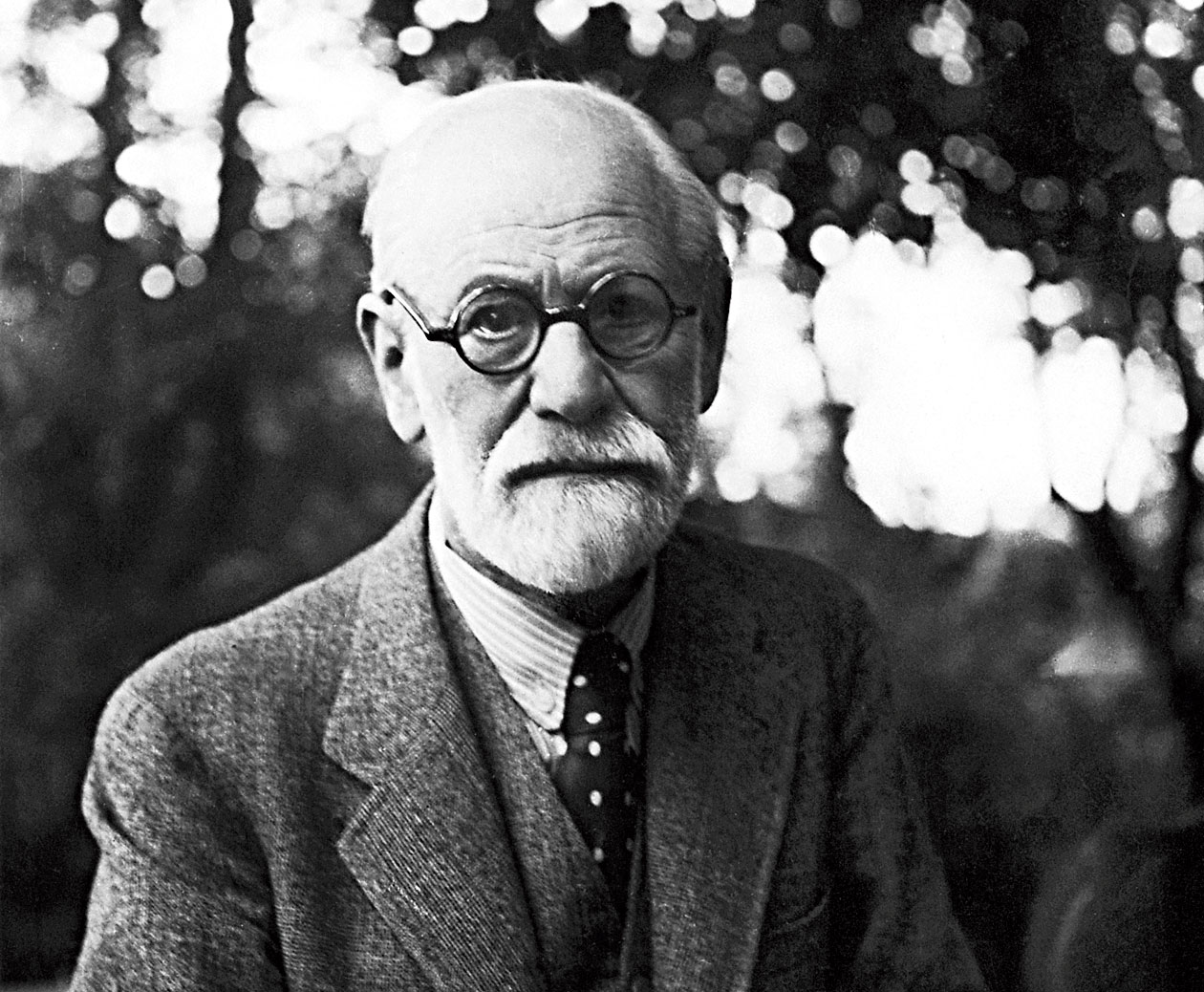

For ancient Stoics like Chrysippus, as well as for the founders of the 20th-century cultic practice of psychoanalysis, the explanations for the origins of feelings were limited to the presumption of an ability they considered a sui generis condition in humans — the mysterious (largely unconscious) ability to emote and feel, as responses to conditions of internal and external stimuli, which they assumed were structured at some deeper level like a language, and therefore, manifestly readable on the couch. Since these felt, unconscious responses are less likely to be witnessed in animals — unless they are caused by “misplaced” mental associations or anthropomorphizing acts of oversensitive witnesses, so went the assumption (19th-century zoologists first severed the vocal cords of live monkeys on their dissection tables to prevent their minds going haywire for this precise reason) — humans have long stayed content with the study of feelings as exclusive to their being in the world. The Strange Order of Things differs, as it tries to understand the phenomena of feeling within the broader field of life and evolution.

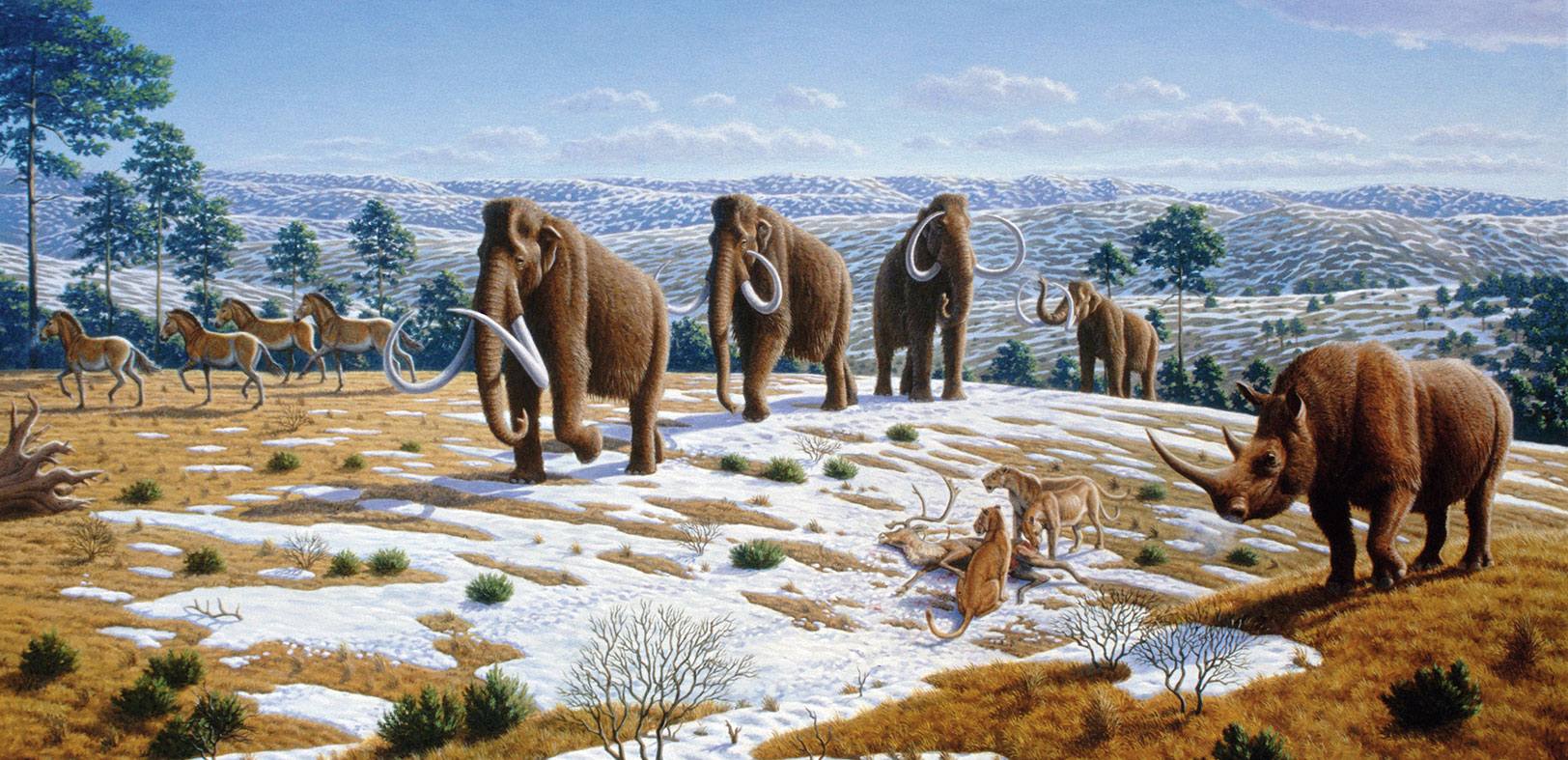

For Antonio Damasio — a professor of neuroscience with a strong fascination for evolutionary biology — feelings have their origins in a region of life that precedes the “collective unconscious” of the first humans wandering across the frozen seas of the Pleistocene; and of the first mammals and reptiles, even. One of the central concerns of his book is that, if feelings have become what they are now — “motives, monitors, and negotiators of human cultural endeavors” — they need to be set in perspective with regard to evolution, in order to understand why they happen. Feelings, in themselves, have strong evolutionary roots reaching back across millennia to a time when ancient unicellular life forms shaped and reshaped themselves in the dark, frothing oceans of a sunless water-world, thoroughly devoid of mind and consciousness, but, as Damasio argues, not totally, devoid of feeling: “the human unconsciousness literally goes back to early life-forms, deeper and further than Freud or Jung ever dreamed.”

Circa 1935: Sigmund Freud (1856 - 1939) the neurologist and founder of psychoanalysis Photo by Hans Casparius

The seemingly irreconcilable idea of feeling existing without complex biological or neural apparatuses is explained by Damasio as pertaining to a “strange order” intrinsic to life itself, which began about 3.8 billion years ago with the first organic cell — “an extraordinary assembly of chemical molecules with particular affinities and ensuing self-perpetuating chemical reactions, ticking, beating, repeating cycles.” With all the post-humanist excitement about artificial intelligence and the algorithmic replication of natural organisms (behind which seems to lurk, according to Damasio, misplaced Cartesian ideas of context and substrate independence), modern science has yet, for better or for worse, failed to recreate that process. Primordial bacteria obviously had no minds, but they sensed and responded: exhibited affinity signals that signified a living presence and “felt” returning signals — “a beginning of the sort of perceptual process that, over time, once nervous systems came onto the scene, would indeed lead to analog representations of the world surrounding nervous systems and serve as the basis for minds and eventually subjectivity.”

The greater part of this book — from what the reviewer has been able to understand — consists of Damasio’s long-winded attempts to explain the substrate of all life on this planet as a particular kind of organized chemistry that started with unicellular life, and subject to what he calls the “homeostatic imperative”: the peremptory, unconscious urge within every living organism to take “a relentless plunge into the future”, no matter what; to feel and to persist, for the sake of the survival of its life. Feelings act as “deputies of homeostasis”, he explains; they appear as catalysts for the biochemical, later complex neural architectures that would eventually trigger human cultures as well as intellectual inventions like the arts, philosophical enquiry, religion, moral codes, political governance, economics, and scientificity.

Although Damasio gives occasional nods to certain philosophers, he avoids a thorough engagement with philosophical investigations of emotion, feeling and consciousness. In a way, this is surprising, especially after the confusion in one’s thought processes that are bound to follow his whirligig explanation of the “making of cultures”. The book runs the risk of physiological reductionism in its claim that the object of all feelings (in insects, animals and humans alike) is the subject’s biological entity. The self-as-subject and self-as-knower are without doubt biologically inseparable in humans, but the self-as-knower (the sense of that strange “I” feeling in you and me, dear reader) is a far more elusive presence; far less discernible in our mindful acts of reading life. We are yet to understand our feelings of sadness and longing, when our minds take flight in search of lost birds and dead people, yet alive.

The Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures By Antonio Damasio, Pantheon, Rs 799