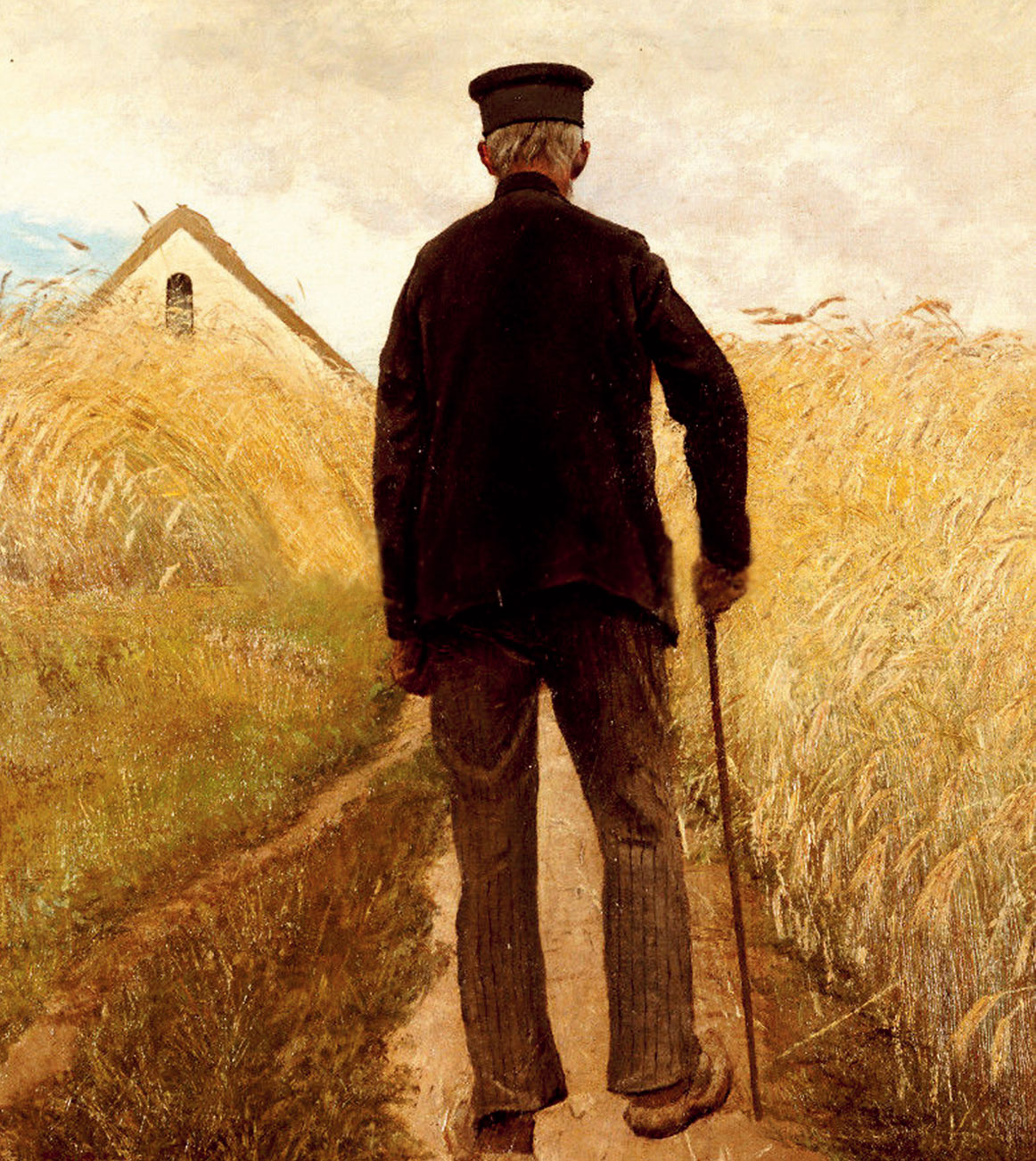

They are becoming a rarity, walking sticks are. And by walking sticks I mean, of course, those good old lengths of wood, the gift of trees, groves, forests. The kind our grandparents, and those of their and earlier generations used when they went out and, on returning home, carefully placed in a chosen corner between two walls, or in their own very special stands. Their users were not necessarily old or infirm. They just felt good having that appurtenance on them.

Shepherd’s crooks are among the earliest forms of this fascinating contrivance, curled to a point at the handle, to guide flocks of sheep and to protect them against predators and also help the shepherd maintain balance on hillsides, sheep’s favourite grazing terrain. Christ, in his shepherd’s role, is depicted holding one. And William Blake has illustrated his tender poem, The Shepherd, by a shepherd holding his crook, surrounded by a gathering of fleece.

At the other end of the pole is the lathi, notorious for the ‘charge’, meant to scare and capable of worse.

That too is a cousin of the walking stick.

Men, rather more than women, have used walking sticks. Why this imbalance I cannot understand but there it is. Proving the rule, exceptions in India include Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, who carried one very gracefully, as did her niece-in-law, the other ‘lotus’, Padmaja Naidu, in her later years.

That walking stick, a thing of beauty and utility, is in retreat, being replaced by the vastly more efficient, firmer, lighter metal tube with ‘features’ like extensions, straps, adjustable grips, lights, wheels, and, most importantly, four feet. But great as these appliances are, in terms of practical use, they are devoid of personality. Each is like the other, manufactured by a machine, mass-produced, steel-cold. The walking stick, on the other hand, is part of the user’s personality. And it acquires something of that, itself. Some of the fancier ones used to have secret recesses to hold a peg of alcohol, tobacco, perfumes, all reflecting the owner’s personality traits and, withal, their hidden indulgences. Good for the user!

Monks use them in Buddhist, Jaina and Hindu tradition, perhaps as part of the accoutrements of renunciation, like the begging bowl or kamandala. Swami Vivekananda’s staff is integral to our image of that transformational being. He used it with zest in his travels, including that to the United States of America. When he left the Woods’ residence in Salem, Massachusetts, in August 1893, Vivekananda, then just 30, gave his staff, described as “his most precious possession”, to his host and his blanket to Mrs Woods, saying: “Only my most precious possessions should I give to my friends who have made me at home in this great country.”

And monarchs have, as well.

Queen Victoria who needed and used a cane, was gifted many of them by her doting subjects so that, The West Gippsland Gazetteer (Australia) reported on October 4, 1898 there was in her palace one room entirely filled with walking sticks. Her Majesty, however, used but one cane being, the Gazetteer reported, “one of great historic value having been presented to King Charles II... cut from on oak tree”. The report went on to say, citing Court sources, that the cane had a gold head “which was rugged and apt to hurt the hand” and so Her Majesty had it replaced. What with? “An idol which graced the temple of an ill-fated Indian prince... an exquisitely wrought affair in ivory... The eyes and forehead are jewelled and on the tongue is the rarest of rubies.” By the description, one can guess who the ‘icon’ was — or is.

The cane was used famously by her great counter-point in India, Lokamanya Tilak. His cane, ever with him in statues of the great man, is no ordinary cane. It is him. It symbolizes his defiance, his dignity. One can imagine him thumping the ground with it while proclaiming, “Swaraj is my birth-right and I shall have it.” In the famous 1910 picture of the Lal-Bal-Pal trio, none of them old by any means, seated, Lala Lajpat Rai (45) holds a slim cane elegantly at its collar, Lokamanya Tilak (54) holds his sturdier one at the handle, only Bipin Chandra Pal (52) for some reason does not carry his. (He used one, as other photographs of his show.)

Did Rabindranath Tagore use a walking stick? Tagore scholars would know. Be that as it may, his poem At the Last Watch, has immortalised that artefact: “Suddenly I found you had left behind by mistake/ Your gold-mounted ivory walking stick./ If there were time, I thought,/ You might come back from the station to look for it,/ But not because/ You had not seen me before going away.”

The cane has been used assertively. Tagore, in his short story, “Didi”, has this passage: “...From time to time Jaygopal tried to interrupt, but the Magistrate, flushed with anger, snapped at him to shut up and, pointing with his cane, directed him to stand up from his stool...” (translated by William Radice).

If we cannot conjure Churchill without his cigar, we cannot imagine him without his cane either. One auction put up a walking stick for sale with an indistinct inscription: “Once owned by Sir Winston Churchill, Home Sec”. The most famous British prime minister had been home secretary from 1910-1912. His successor, Clement Attlee, was a walking-stick user too, as was the man who could have become a great Labour prime minister if only he was not so far to the Left, and not so deliberately wind-blown in his appearance, Michael Foot. The great socialist’s grand-nephew, Tom Foot, wrote in The Independent, shortly after Foot’s death: “The support of his wife, the film-maker Jill Craigie — and, after she died, of her friend Jenny Stringer, who came every day to check on him in his final 10 years — were perhaps matched in constancy only by this gnarled larch staff.” The Michael Foot cane was most appropriately auctioned for a stone bench memorial in Plymouth, in the Devonport constituency he represented.

Gandhi’s plain staff is famous, as is Maulana Azad’s sharp-ferruled cane now on view in the Azad Museum in Calcutta, and that of Babasaheb Ambedkar. V.K. Krishna Menon was a user and collector of walking sticks. One anecdote has Menon, enraged by an impudent question at a press conference in London, hurling his walking stick at the journalist.

Perhaps the most famous of all canes is the screen Charlie Chaplin’s seemingly elastic bamboo cane, symbolizing everything about it — utility, beauty, eccentricity. When I was working in Oslo, I used to make it a point to gaze at an adorable statue of the great man whenever I crossed Majorstua, and in particular at the bent-to-breaking cane. I was dismayed one day to find the cane gone. A vandal had broken and removed just that bit of the statue. Never has that lord of laughter looked so woebegone as that Charlie.

But ‘stealing’ happens in many ways. Or does not happen. As a district officer in Tamil Nadu, I once saw from my jeep an old man walking across a dusty field, holding a gnarled walking staff. It was made, obviously, from a tree branch. I got down to speak to him. He looked at me, startled, through his thick dust-laden lenses.

“Ayya, Vanakkam... Nothing... nothing... Just saw that walking stick of yours... It is lovely.”

“Ye...s.”

“Must be very old.”

“Ye...s.”

“Can you... I mean, can I... ask you if you can... please... give it to me... I am trying to collect used walking sticks.”

He was uncomprehending. I had to repeat my request. He then laughed, bending over. I thought I had struck gold or rather, wood. But, no. He straightened up and, looking with a mixture of self-pride and utter contempt at me, my jeep, my liveried attendants, said, “Swami... I would not part with this for anyone... It is not a stick... It is my life.” I scrambled back to my jeep feeling like dust, the dust under his proud staff.

The walking stick is much more than what its name suggests. It is a symbol of its user’s determined dignity in self-reliance.

To end with a ‘missing’ walking stick. I asked that personification of dissent and independent-mindedness, that nonagenarian, Acharya Kripalani, why he did not use one. “I am short-tempered, that is why.” May his non-existent walking stick hover over all those who trifle with individual and collective liberties!