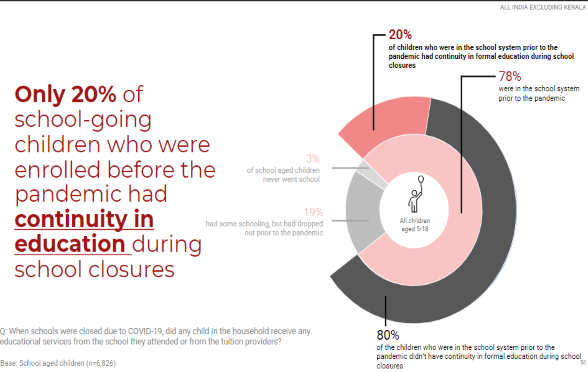

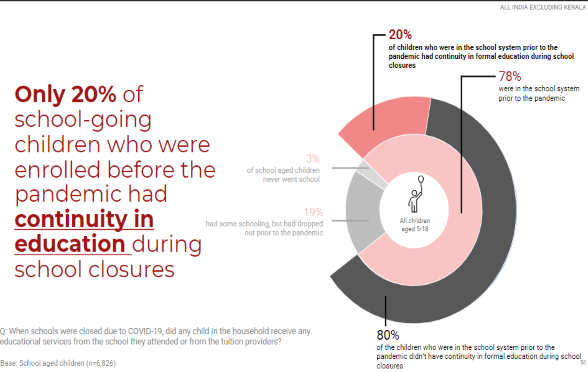

During school closures, 80% children left without access to education: Survey

A national survey has shown that only 20% of school-aged children (between five and 18 years) enrolled in the formal education system have received remote education during COVID-19 induced school closures.

The survey, titled “Access to services during COVID-19 in Digital India” was conducted by LIRNEasia, a regional think tank working on digital policy issues across the Asia Pacific, and Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), a policy-oriented economic policy think tank based out of New Delhi.

Its findings were released at a virtual launch event on November 12. The study has been funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), through a joint grant given to three regional think tanks in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

The 2021 survey showed that access to education was greater among students residing in urban areas, from wealthier families, with more educated household heads, and in higher grades.

Many of the 20% who were able to access education during school closures did so through multiple channels. However, these students’ experiences were heterogeneous. Only 55% of students (of this small group who received some education) participated in live (real time) online lessons, while 68% watched recorded video lessons and 75% had information and assignments communicated to their smartphones through channels such as WhatsApp.

It is also noteworthy that 58% of these students also had contact with schools through offline channels, with information and assignments being physically delivered to their homes.

The other 80% of children, however, were left behind.

The challenges faced by those receiving and not receiving education also differed. The parents of those who received education said their key challenges were their children not being attentive, schools being unprepared to deliver online education and high data costs.

Meanwhile, the most cited challenges of those who didn’t receive education were poor connectivity (3G and 4G signal) in their area, and insufficient devices at home to meet the competing needs of all their family members.

LIRNEasia CEO Helani Galpaya said, “The pandemic made the education gap worse, impacting students from disadvantaged households the most. But it wasn’t just a connectivity problem ̶ schools were caught off-guard and were not prepared to deliver online lessons in the first round of lockdowns. Luckily, things did improve in the subsequent shut downs. But unless a mix of real-time online and self-directed learning and meaningful feedback is provided, the learning gaps probably were not bridged.”

Rajat Kathuria, senior visiting professor at ICRIER, added, “School children were amongst the most affected by the pandemic. Our survey findings confirm the widening of the education divide as several households without internet devices were unable to organise remote learning for their children. Even where devices and connectivity were available, the system took time to adapt to online learning. Education policy needs much more than network infrastructure for material impact on learning outcomes.”